Izvestiya soigsi. Ossetian literature

Ossetian language (Ossetian iron jvzag) is the language of Ossetians. It belongs to the eastern subgroup of the Iranian group of the Indo-Iranian branch of the Indo-European languages. Distributed in the Republic of North Ossetia-Alania and in South Ossetia. The number of speakers is estimated at 450-500 thousand people, of which in North Ossetia - approx. 300-350 thousand people.

The modern Ossetian language was formed as a result of a mixture of the Iranian-speaking population of the foothills of the North Caucasus, who left the invasions of the Tatar-Mongols and Tamerlane in the mountains of the Central Caucasus, with the aboriginal population already living in this area (who, presumably, spoke the language of the Caucasian language group). As a result, the language was enriched with phenomena unusual for Indo-European languages in phonology (stop-laryngeal consonants), in morphology (developed agglutinative case system), in vocabulary (words with obscure etymology and clearly borrowed from the Adyghe, Nakh-Dagestan and Kartvelian languages).

The Ossetian language retains traces of ancient contacts with the Turkic, Slavic and Finno-Ugric languages.

Writing

Based on the analysis of the Zelenchuk inscription, it can be assumed that the ancestors of the Ossetians - the Caucasian Alans - had a written language already in the 10th century.

The Zelenchuk inscription is characterized by the constant transmission of the same Ossetian sounds by the same Greek signs, which indicates the existence of well-known skills and traditions in this area. (Gagkaev K. E. Ossetian-Russian grammatical parallels. Dzaudzhikau: 1953. P. 7)

Until the second half of XVIII century there is no information about Ossetian writing.

In order to spread Christianity among Ossetians, Ossetian translations of religious texts began to appear by the end of the 18th century. In 1798, the first Ossetian printed book (catechism) was published, typed

Cyrillic alphabet. Another attempt to create writing took place 20 years later on the other side of the Caucasus Range: Ivan Yalguzidze published several church books in the Ossetian language, using the Georgian Khutsuri alphabet.

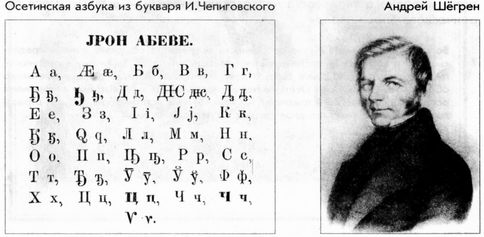

Modern Ossetian writing was created in 1844 by a Russian philologist of Finnish origin Andreas Sjogren. In 1923-38 it was transferred to the Latin basis, since 1938 in North Ossetia - Russian graphics, in South Ossetia - the Georgian alphabet (since 1954 - Russian graphics). During the transition to Russian graphics in 1938, a number of symbols of the Sjögren alphabet were replaced by digraphs (dz, j, xb, etc.), of the symbols not included in the Russian alphabet, only the letter zh remained. The letter Zh/zh is an unmistakable determinant of Ossetian texts: of all the Cyrillic alphabets, it is only in Ossetian.

The modern Ossetian alphabet includes 42 letters, and some of them (ё, sh, ь, я, etc.) are found only in borrowings from (or through) the Russian language.

Dialect articulation

Two dialects are distinguished in the Ossetian language - Digur (spread in the west of North Ossetia-A)

and Irun - the differences between them are significant. Speakers different dialects usually do not understand each other well if they do not have sufficient experience in communicating in a different dialect. Usually, speakers of the Digor dialect (about 1/6 of the speakers) also speak Iron, but not vice versa.

In the Iron dialect, the dialect of the inhabitants of South Ossetia stands out (the so-called "Kudar" or "Yuzhansky"), characterized by regular transitions of consonants (dz to j, etc.) and the quality of the front vowels. In the southern dialects there are more Georgian borrowings, in the northern dialects there are Russian roots in place of the same borrowings (for example, “rose” in the north is called rozzh, and in the south it is Wardi).

The literature describes a more fractional division into dialects, but in modern conditions there is a leveling of minor differences in the mixed population of cities and large villages.

Until 1937, the Digor dialect of the Ossetian language in the RSFSR was considered a language

a special alphabet was developed for it, a serious literary tradition was founded. However, in 1937 the Digor alphabet was declared “counter-revolutionary”, and the Digor language was again recognized as a dialect of the Ossetian language (see Revolution and Nationalities, 1937, N 5, pp. 81–82).

There is a literary tradition in the Digor dialect, the Digorzh newspaper and the Irzhf literary magazine are published, a voluminous Digorsk-Russian dictionary has been published, and the Digorsky Drama Theater is operating. The Constitution of the Republic of North Ossetia-A in essence

recognizes both dialects of the Ossetian language as the state languages of the republic, in Art. 15 says:

1. The official languages of the Republic of North Ossetia-Alania are Ossetian and Russian.

2. The Ossetian language (Iron and Digor dialects) is the basis of the national identity of the Ossetian people. The preservation and development of the Ossetian language are the most important tasks of the state authorities of the Republic of North Ossetia-Alania.

The basis of the literary Ossetian language is the Iron dialect (with minor lexical borrowings from Digor). The founder of Ossetian literature is the poet Konstantin Levanovich Khetagurov (Ossetian Khetagkaty Kosta).

Grammar

The Ossetian language is one of the few Indo-European languages that have long existed in the Caucasus. Having been influenced by Caucasian and Turkic languages he got rich interesting phenomena, which are not, for example, in Russian. Among these "curiosities":

a rich system of agglutinative declension, unusual for Iranian languages;

twenty decimal account;

three tenses in the subjunctive mood of the verb;

lack of suggestions active use postpositions

and others.

Phonology

The total number of phonemes in the modern Ossetian language

35: 7 vowels, 2 semivowels, the rest are consonants.

Ossetian stop-laryngeal consonants do not have a correspondence in Iranian languages (indicated in writing as kb, pb, tb, cb and ch). Especially often these consonants are found in Caucasian borrowings and in words with obscure etymology (presumably substrate): kuyri "week", chiri "pie", chyr "lime", bit'yna "mint", etc.

The stress is phrasal (syntagmatic), falls on the first or second syllable of the syntagma, depending on the quality of the syllable-forming vowel in the first syllable.

Morphology

Agglutinative declension of names (there are 9 or 8 cases, depending on the criteria; a rich case system is presumably Caucasian influence) and inflectional conjugation of the verb.

The plural is formed regularly with the suffix -t- (in the nominative case with the ending -ae):

lag "man" - lagta "men", dur "stone" - durta "stones". When forming the plural

alternations are possible in the basis: chinyg "book" - chinguyta "books", zarag "song" - zarzhyta "songs".

The most common grammatical tool, as in Russian, is affixation (suffixation in more than prefix).

Researchers

Andrei Mikhailovich (Johann Andreas) Sjogren. Creator of the Cyrillic Ossetian alphabet. He owns the first Scientific research Ossetian language, published in St. Petersburg under the title "Ossetian grammar with concise dictionary Russian-Ossetian and Ossetian-Russian”.

Vsevolod Fedorovich Miller. Outstanding Russian folklorist and linguist. Author of "Ossetian studies" (1881, 1882, 1887).

Vasily Ivanovich (Vaso) Abaev(1899–2001). He wrote many works on Ossetian and Iranian studies. Compiled a 4-volume

"Historical and etymological dictionary of the Ossetian language" (1957–1989).

Mohammed Izmailovich Isaev. Iranist and Ossetian; in particular, the author of the book "Digor dialect of the Ossetian language".

From Wikipedia.

The famous Ossetian poet Kosta Khetagurov, whose biography is given in this article, lived and worked at the end of the 19th century. He was also a publicist, playwright and painter. He is considered the founder of all Ossetian literature.

The value of the poet's work

Kosta Khetagurov, whose biography is full of interesting facts, was born in 1859 in the mountain village of Nar in North Ossetia.

He is the recognized founder of the Ossetian literary language. For this people it has the same meaning as Alexander Pushkin for Russian literature.

His first famous collection was published in 1899. It was called "Ossetian lira". For the first time in history, poems for children written in the Ossetian language were published in it.

At the same time, Kosta Khetagurov also wrote a lot in other languages. The biography of the poet is also interesting to the Russian person, since he composed many works in Russian. He actively collaborated with the periodicals of the North Caucasus. His essay on ethnography called "The Person" was very popular.

The first Ossetian poet

It is worth mentioning right away that the leadership of this Ossetian poet has been disputed more than once. A brief biography of Kosta Khetagurov contains information that the first major poetic work in Ossetian was published by Alexander Kubalov. He was 12 years younger than Khetagurov.

In 1897, Alexander wrote the poem "Afhardty Hasan". This work is close in spirit and style to folklore, oral folk art. It is dedicated to the custom of blood feud, popular among the mountain peoples. Moreover, this tradition is condemned in the poem. For many years, this particular work was considered the best of what was written in the Ossetian language.

Kubalov was a representative of Ossetian romanticism. He translated poems by Byron and Lermontov. His fate ended abruptly and tragically. In 1937, during the period of Stalinist repressions, he was arrested. He is believed to have died in custody in 1941.

At the same time, Kosta Khetagurov officially remains the main Ossetian writer. His biography proves that he made a much greater contribution to the further development of Ossetian literature.

Khetagurov's childhood

The biography of Kosta Khetagurov originates in the family of the ensign of the Russian army Levan Elizbarovich Khetagurov. The hero of our article practically does not remember his mother. Maria Gubaeva died shortly after giving birth. The boy was raised by a relative of his father, Chendze Dzeparova.

Five years after his wife's death, Kosta Khetagurov's father brought a new woman into the house. The biography of the poet briefly tells about his stepmother, who was the daughter of a local father and did not love her adopted son. Therefore, the boy spoke coldly about his father's new wife, often running away from home to distant relatives, with whom he had a more sincere relationship.

Poet's education

Extremely popular in his homeland is the Costa Khetagurov. A biography in Ossetian tells in detail what kind of education the hero of our article received.

He went to school in his native village of Nar. Soon he moved to Vladikavkaz, where he began to study at the gymnasium. In 1870, together with his father, he moved to the Kuban region with the capital in Yekaterinodar (today it is Krasnodar). Levan Khetagurov moved the entire Nar Gorge to the Kuban, he was the leader of the local Ossetian dynasty. In the new place, the settlers founded the village of Georgievsko-Ossetian. Today it is renamed in honor of Khetagurov Jr.

The biography of Kosta Levanovich Khetagurov contains one amazing fact. Somehow he missed his father so much that he fled to him from Vladikavkaz to a distant Kuban village. After that, his father was able to arrange him only in the primary village school in Kalanzhinsk. And that with great difficulty.

In 1871, Costa entered the provincial gymnasium in Stavropol. Here he studied for ten years. Several early texts of the poet have come down to us from this period of his life. The poem "Vera", written in Russian, and two poetic experiences in Ossetian - "New Year" and "Husband and Wife".

Success in creativity

The biography of Kosta Khetagurov in Ossetian tells how his artistic talent was appreciated back in the early 1880s. In 1881 he was admitted to the prestigious Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg. He studied with the master of genre and portrait painting Pavel Chistyakov.

However, the study was not entirely successful. Two years later, he was deprived of his scholarship, as a result, he was left practically without a livelihood. He had to leave the academy, and soon return to Ossetia.

Khetagurov begins to live permanently in Vladikavkaz. Until 1891, he creates most of his famous texts. Mostly in Ossetian. Published in the all-Russian and local press, in particular, in the newspaper " North Caucasus", which was released in Stavropol.

Link

What else is Khetagurov Kosta Levanovich known for? His biography is similar to the story of Pushkin. Both are considered the founders of the literary language of their people, both were sent into exile for excessively freedom-loving poems.

The hero of our article ended up in exile in 1891. He was expelled from Ossetia. By 1895 he settled in Stavropol. At the newspaper "Northern Caucasus" he published his own collection of essays in Russian.

Illness and death

In those same years, doctors made a disappointing diagnosis for Khetagurov - tuberculosis. He is undergoing two surgeries. In 1899 he arrived at the place of official exile in Kherson. In the local climate he feels very bad, he constantly complains about dust and stuffiness. And also to the fact that there is no one to communicate with, it is impossible to meet a single intelligent person. According to Khetagurov, only traders and merchants are on the streets.

In this regard, he asks for a transfer to Odessa. He is denied this, agreeing to let him go to Ochakov. This is a town in the Nikolaev region (Ukraine). Khetagurov finds shelter in the family of the fisherman Osip Danilov. He is conquered by the sea, which is already visible from the windows of the hut. During these months, the hero of our article regrets only that he did not take paint with him to capture the beauty of these places.

In Ochakovo, rumors reach him that his collection "Ossetian Lira" has been published in his homeland. True, not in the form in which it was expected. The royal censors could not allow these verses to be printed as they were. As a result, many texts were reduced or changed beyond recognition, others were not included in the poetry collection at all. The censors were confused by their revolutionary content.

Khetagurov's condition did not improve. Including due to the fact that the period of his stay in Ochakovo ended, and he had to return to Kherson, which he hated.

In December 1899, the link was finally abolished. Faced with transport problems, Costa left Kherson only in March of the following year. To begin with, he stopped in Pyatigorsk, and then moved to Stavropol to resume the publication of the newspaper "Northern Caucasus".

A serious illness struck Khetagurov in 1901. She prevented him from finishing his important poems - "Khetag" and "Weeping Rock". At the end of the year, he moved to Vladikavkaz. Here his health deteriorated sharply, and Costa was chained to the bed.

All friends and acquaintances of Khetagurov noted that all his life he cared little about himself, about his well-being. Only at the end of his life he tried to start a family, build a house, but did not manage to do anything.

On April 1, 1906, he died in the village of Georgievsko-Osetinskoye, stricken with a serious illness and constant persecution by the authorities. Later, at the insistence of the Ossetian people, his ashes were transported and reburied in Vladikavkaz.

Key works

The first major work that forced critics and readers to pay attention to the young writer, Khetagurov wrote when he was studying at the Academy of Arts. It was the play "Late Dawn", a little later another dramatic work came out - "Attic". True, contemporaries noted that both plays were not perfect in their artistic form. It was one of the first literary experiences of the author.

In "Late Dawn" the novice artist Boris is in the foreground. He is young, progressive and even revolutionary. He decides to devote his life to the liberation of the people. For this, he even rejects his beloved, explaining his choice by the fact that he wants to serve the people. To do this, he seeks to leave St. Petersburg in order to work exclusively for the common good. His fiancee Olga is trying to dissuade her lover, considering the dream of universal equality as utopian nonsense. Olga convinces Boris that it is his duty to serve society with his talents. At the end of the play, Boris nevertheless leaves the city on the Neva. He goes to the people.

"Mother of Orphans"

To understand the problems of Khetagurov's lyrics, the poem "Mother of Orphans" from the collection "Ossetian Lira" is well suited. This is a vivid example of Ossetian poetry performed by Costa.

In the text, he describes one of the usual evenings of a simple mountain woman with many children, who was left a widow. She is a native of his native village Nar.

In the evening, a woman has to fiddle with a fire while five hungry and barefoot children frolic around her. Mother is consoled only by the fact that very soon dinner will be ready, for which everyone will receive their portion of beans. Instead, exhausted and tired children fall asleep without even waiting for food. The mother weeps as she knows that eventually they will all die.

This work vividly shows the poverty and deprivation in which ordinary Ossetians live. This was one of the main themes of Khetagurov's work.

13.10.2015

Founder of Ossetian literature, great poet, artist and public figure Khetagurov Kosta Levanovich was born on October 15, 1859 in the village. Nar of North Ossetia in the family of an officer of the Russian army.

The poet invariably had deep respect for his father. “I not only loved my father, but idolized him.” The father's influence on the future poet was purely moral; cultural and ideological continuity was out of the question. And Costa did not remember his mother at all. Costa's mother died when the boy was two years old. The future poet studied at the Stavropol gymnasium. Here he first got acquainted with the work of Russian writers, began to paint, write poetry.

In 1881, K. Khetagurov, with the help of art teacher V. I. Smirnov, entered the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts, where he studied until the summer of 1885. Years of study in the capital played a big role in the formation of Kosta Khetagurov as a poet and revolutionary democrat. He was associated with secret youth circles, whose activities were directed against the existing system. It was not possible to graduate from the Costa Academy of Arts due to the extremely poor situation. He returned to the Caucasus and lived and worked in Vladikavkaz until 1891. He writes poetry, poems, journalistic articles, which are published not only in the Caucasian newspapers, but also in the periodicals of the capital. The poet exposes the colonial policy of the tsarist authorities, expresses the innermost thoughts and feelings of the people, calls them to fight for freedom. For this, K. Khetagurov was subjected to constant persecution by the Terek administration.

The poet wrote in Russian and Ossetian. The first collection of his Russian poems was published in 1895 in Stavropol, and in 1899 his famous Iron Fandyr (Ossetian Lyre) was published in Vladikavkaz - a book of poems written in the Ossetian language. This book, according to the apt expression of N. Dzhusoyta, is "the most complete and most brilliant manifestation of the spiritual forces, the artistic genius of the Ossetian people."

The works of K. Khetagurov were repeatedly published and republished both in Ossetian and in the languages of many peoples of our country and abroad.

In 1959-1961. The publishing house of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR published a collection of the poet's works in 5 volumes. This is the most complete edition of the literary heritage of Kost Khetagurov.

Orphan childhood, like an inescapable pain, forever remained in the memory of the poet. The image of a mother and childhood not warmed by maternal caress runs like a leitmotif through all his work. The moral, psychological and initial aesthetic formation of his artistic individuality took place here, in the mountain environment, in the Nar basin. The subtlest feeling of the native language and its intuitive and cultural development took place outside of Ossetia and not on Ossetian soil.

On November 1, 1871, Costa was enrolled in the preparatory class of the Stavropol Men's Classical Gymnasium and assigned to a boarding school with her. Kosta studied at this gymnasium for ten years, then entered the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts in the fall of 1881, receiving one of two scholarships that were paid by the administration of the Kuban region from mountain fines. It was not possible to graduate from the Costa Academy: in January 1884, the authorities of the Kuban region stopped issuing scholarships. Costa attended classes at the academy as a volunteer for another 2 years, but in the summer of 1885 he was forced to return to his father's house. Not having completed the full course of study.

The active nature of the young poet and artist was looking for a sphere of application for the talents awakened in him, and he moved to Vladikavkaz. Costa's move was also due to the fact that he spent many years away from native land and now he was drawn to his homeland, to his native linguistic and cultural element. He stayed in Vladikavkaz for almost six years. But he could not really show his versatile abilities. Costa wrote poems, poems mainly in Russian. He also worked as a painter, exhibited his paintings together with the Russian artist A. G. Babich, painted theatrical scenery, arranged amateur literary and musical evenings, and occasionally published his Russian works in the Stavropol private newspaper Severny Kavkaz. In newspaper reports, Costa's speech looked like the most striking episode of the entire holiday, but the poem dedicated to the memory of Lermontov was not allowed to be printed by censors; it was published, and even then anonymously, only ten years later. The reaction of the censorship is understandable: the Ostenin poet saw in Lermontov a “harbinger of the desired freedom”, a “noble powerful force” raising people “to fight for a great, honest cause”, and the organizer of the celebrations wanted to drown out the protesting voice of Kost with praises as the organizer of the struggle for the Ossetian school, was exiled by order of the head of the Tersoy region outside his native land for a period of 5 years. In June 1891, Kosta left Vladikavkaz for the village of Georgievsko-Osetinskoye to visit his elderly father. Began, perhaps, the most difficult time in the life of the poet. Now he was completely excluded from the social environment and doomed to lead a miserable existence: he was no longer and could not be a simple peasant, and he had no opportunity to apply his knowledge and talent to any important and worthy business. The matchmaking for the long and dearly beloved girl Anna Alexandrovna Tsalikova ended with a polite refusal. The poet's father has died. He spent almost 2 years in the wilds of Karachay Costa. Only in February 1893 did he manage to move to Stavropol and become a permanent contributor to the Severny Kavkaz newspaper. Costa worked in this edition until 1897. And these years were the time of the most intense creative and social activity of the Ostenin poet. In four years, he turned from a provincial obscure poet into a prominent literary figure of his time. All these years, Costa wrote not only in Russian. His Ossetian works were mostly written at the same time, but he could not publish them - there was still no Ossetian press, no Ossetian book publishing. However, the poet worked hard to improve his works, included in the book "Iron Fadyr". In July 1897, Kosta Khetagurov was forced to undergo an operation. It went well, but tuberculosis of the hip was not defeated. In October, the poet had to go to St. Petersburg and again turn to the doctors. On November 25, he underwent a severe operation, after which he did not get out of bed for six months. In June 1898, Costa returned to his homeland, where he continued his treatment. V. I. Abaev, a great connoisseur of the life and work of the poet, said about him: "Kost had his own Benckendorff - General Kakhanov." The first eviction of the poet outside the Terek region was the work of this provincial Benckendorff. Costa appealed against the arbitrariness of the presumptuous official. And he began to look for a reason for a new exile of Costa, who had annoyed the all-powerful boss with his articles and satirical works.

On May 26, 1899, Costa was already on his way to the place of his new exile. Upon his return to the Caucasus in March 1900, Costa again began to collaborate in the periodicals of Stavropol. Pyatigorsk and Vladikavkaz. His journalism became even more acute and problematic. He spoke no less actively than in the heyday of his journalism. And it seemed that a new, more mature period of his work had begun, but it soon became clear that the poet's strength was running out, that his health was irreparably broken.

In December 1901, Kosta moved to Vladikavkaz, deciding to settle here forever. He takes an active part in all local cultural and educational events. Engaged in painting. Publicism, continues to work on the poem "Khetag", tries to open a drawing school for gifted children, proposes to take over the editing of the newspaper "Kazbek". However, all these initiatives remained unfinished or unfulfilled. By the end of 1903 Costa. Sick and lonely, spent in an unheated apartment, deprived not only of medical care, but also of elementary supervision.

In January 1892, Costa was to endure even more severe blows of fate.

Material difficulties were so hopeless that the proud Costa sometimes had to ask friends for bread. In the summer, his sister came for him and took him to his native village. The poet lived for three more years. But he could no longer return to creative and social activities. On March 19, 1906, his noble heart stopped beating. During the life of the poet, few people understood the true significance of Costa's artistic creativity and social activities. But when he was gone, it was clearly revealed that a man of extraordinary talent, wisdom and courageous character had left.

Kosta began to write poetry while still at school, writing in Russian and Ossetian, and during his youth, mainly in Russian. He did not know Ossetian reality. I could not judge her and live with her anxieties. The mature period in Costa's work came shortly after his return to his homeland in 1885. This was the time of the poet's direct confrontation with the terrifying Ossetian reality. Poverty and lawlessness. Age-old ignorance and spiritual depression of the people led him to despair.

The poems "Fatima", "Before Judgment", "Weeping Rock", the ethnographic essay "The Person" - all these works are devoted to the analysis and assessment of the contradictions of the recent past of the Ossetian people.

In his thoughts about the past, Costa was always consistent, and his position was strictly thought out. The patriarchal-feudal past of the highlanders did not contain freedom - this is his main premise, and it is affirmed by him both in journalism and in a number of works of art. In this sense, the poems "Before Judgment" and "Weeping Rock" are close to "Fatima"

The poet rejected slander on the national character of the highlanders and defended them from the arbitrariness of the colonial administration and the "unseemly exploitation" of capital. And he defended the mountain peoples of Costa with all the means available to him - a poetic word, a journalistic article, petitions to official authorities, etc. . But Costa's position in assessing contemporary activity was more vivid and complete in his satirical and accusatory poetry, primarily in the poem "Who Lives Joyfully".

There are many satirical motifs in Costa's lyrical poetry. True, officials are not the object of denunciation in his lyrics. And the moral and psychological world of the militant philistinism. The opposition of the poet to the crowd, its way of life and petty-bourgeois ideals of happiness - such is the meaning of accusatory verses in Khetagurov's lyrics. And this position is clearly seen not only in accusatory, but even in a number of intimate lyrical works. And it is expressed in two ways: the poet either openly debunks the petty-bourgeois way of life. Or he opposes his own ideal. The theme of the people is the main theme of all Costa's work, widely developed in his poems. It also combines a small number of poems in Russian. However, they are far inferior in the authentically realistic depiction of the people's fate to Iron Fardyru, the most mature creation of Costa.

"Iron Fandyr" is the only book of poems in the Ossetian language. She wrote to them all her life. It included works created from the summer of 1885 until the end of the poet's career. They were written at different times and on different occasions. There was nowhere to publish them - in Ossetia at that time there was no periodical press. Poems diverged in the lists, some became folk songs, some ended up in school textbooks. But years passed, and the author came up with the idea of a separate book.

However, only on September 3, 1898, the first white manuscript appeared with the subtitle: “Thoughts of the Heart. Songs. Poems and fables.

The release of "Iron Fandyr" in May 1899 was an exceptional event in its significance and consequences in the history of Ossetian national culture as a whole. Ossetian professional poetry received national recognition and became the largest phenomenon in the spiritual life of the nation.

Costa divided all the works into 3 thematic sections: lyrics in the broad sense of the word, fables and fairy tales in verse, poems for children and about children, which at the beginning were supposed to be published separately under the title “My gift to Ossetian children”

Of course, even before Kosta Khetagurov, the Ossetians had a rich and varied art of folk poetry. Before him, Mamsurov Temyrbolat created his songs in his native language, although they remained unknown to Costa, so he himself had to re-create the foundations of national professional poetry. Ossetian folk poetry was that age-old tradition that he was called upon to renew, reform, and raise to the artistic level of developed literatures. The experience of Russian poetry served as a model for him. But he subtly took into account in his art the originality of both of these traditions.

Anthology of Ossetian poetry

In the Parliament of South Ossetia, at the second meeting of the tenth session, the Chairman of the Parliament of the Republic of South Ossetia, Petr Gassiev, made a proposal to present the first Kulumbegov T. G medal to his family. Gassiev noted that the Parliament established the Torez Kulumbegov medal last year. “Torez Kulumbegov deserves it, he was one of the most authoritative political and public figures in our country. You have familiarized yourself with the medal, it is made of pure silver. This medal will not be distributed en masse, and it will be...

28.02.2019

The second meeting of the tenth session of the Parliament of the Republic of South Ossetia took place. The meeting was chaired by the Chairman of the Parliament Petr Gassiev. At the beginning of the meeting, Petr Gassiev awarded the Director of the Tskhinvali Boarding School Roland Tedeev with Honorary Diplomas of the Parliament of the Republic of South Ossetia, “For his great personal contribution to the upbringing of the younger generation, for his sensitive attention to children, responsiveness and mercy” and the head of the Analytics Department of the Information and Analytical Department of the Parliament Republic of South Ossetia Elena Kulumbegova, "For conscientious performance of their duties and assistance in providing...

28.02.2019

Olga Voronova, a member of the Public Chamber Russian Federation, Doctor of Philology, Professor, member of the Russian Military Historical Society, author of the book "Modern Information Warriors: Typology and Technologies". - In the events in Venezuela, all the signs of the classic scenario of "color revolutions" are clearly visible. Let me remind you that "color revolutions" is a technology developed in the United States for coups d'état in conditions of artificially created instability. In accordance with this...

In the building of the South Ossetian State University. A. Tibilov held a round table on the problems of road safety. The event was attended by the Minister of Emergency Situations of the Republic of South Ossetia Alan Tadtaev, the Head of the traffic police of the Republic of South Ossetia Alan Dzhioev, the Chairman of the Public Chamber of the Republic of South Ossetia Anatoly Dzhidzhoev, the Rector of South Ossetia State University Vadim Tedeev, school directors, representatives of the public and other interested persons. The main topics of discussion were the organization of integrated safety for children on the roads, the need to install video cameras and video recorders in crowded places, tougher penalties for...

27.02.2019

Nafi Jusoity would have turned 94 today

When in the historical common destiny of ours again and again the need arises to choose a path, and on the well-worn trajectories of the roads again and again losses, is it really not the time to ask the generations both previous and present - WHAT do we inherit and HOW do we do it? The mechanisms of preservation of traditions and their renewal fail every time when the already very thin, elite layer of the Guardians of Culture metatext organics becomes thinner. About it...

Further development writing and school education. Originating in the 18th century the fundamental foundations of culture - the development of writing, school education, book printing - were perceived by the Ossetian society as natural and the necessary conditions for the life of the people. There were no religious or any other social forces in Ossetia that would have prevented the forms of development of Ossetian culture that were modern for that time. There were also no external "aggressive" political forces that would impose cultural values alien to Ossetia. There was a stable internal predisposition of the people to the perception of the fundamental achievements of European culture. The people were aware of the lagging behind this culture. This awareness, as well as Ossetian belonging to the Indo-European branch of peoples (in the past, Ossetians experienced a powerful cultural evolution) saved Ossetia at a new stage of social development from upheavals in the sphere of culture.

Ossetian society in the first half of the 19th century. showed the ability to integrate achievements both in the field of writing, school education, and fiction and the humanities - areas inaccessible to peoples engaged in organizing the initial forms of cultural development.

At the beginning of the XIX century. there was a further improvement of the Ossetian written culture. On the basis of young writing, first of all, books of religious content appeared, as well as study guides for Ossetian schools. New were the translations of state acts and the involvement of the Ossetian language in the service of the administrative-state sphere. For example, at the beginning of the XIX century. a prominent public and cultural figure of Ossetia, Ivan Yalguzidze (Gabaraev), who spoke excellent Russian, translated into Ossetian the "Regulations on temporary courts and oaths."

Ossetian writing developed on the basis of Russian graphics. At the same time, Ossetia was searching for graphic means that most fully reflected the lexical and phonetic features of the Ossetian language. They tried, in particular, the graphic possibilities of Georgian writing. The same Ivan Yalguzidze, on the basis of Georgian graphics, created the Ossetian alphabet and published in Tiflis the first primer in the Ossetian language.

Ivan Yalguzidze's experience in using Georgian graphics to develop Ossetian writing was also used later. However, the active involvement of Ossetia in the cultural environment of Russia made the Russian language a priority for Ossetians, and with it its written graphics. Another thing was also important - the belonging of the Ossetian and Russian languages to the same Indo-European language branch.

The most popular sphere of cultural life of the Ossetians was school education. In the first quarter of the XIX century. small schools were opened in the villages of Saniba, Unal, Dzhinat and others. Those who graduated from them could continue their studies at the theological school of Vladikavkaz. The children of wealthy parents also entered the Astrakhan and Tiflis theological seminaries, which trained clergy for Ossetia.

In the 30s. 19th century growing interest in secular education. Many pupils of the Vladikavkaz theological school preferred to enter a military or civilian educational institution.

In the dissemination of education, an important place was occupied by schools that functioned under military units - regiments, battalions. They were also called "schools for military pupils", the purpose of which was to educate children of honorary classes. In such schools, children under the age of 17 studied at public expense. Those who graduated from school entered the military or civil service. Among children and parents, the Navaginskaya school, established in 1848 in Vladikavkaz for children of privileged classes, was especially popular.

In Ossetian society, the interest in school education was so great that already in the first half of the 19th century. in Ossetia, the issue of women's educational institutions was discussed. The opening of the first schools for girls dates back to the 50s. 19th century One of them, founded by Zurapova-Kubatiyeva, was a small boarding school for training Ossetian girls into "religious, pious mothers." The same boarding house was opened in Salugardan.

More thoroughly, the question of women's education was raised by Akso Koliev, a priest and inspector of the Vladikavkaz theological school. At his own expense, he opened for Ossetian girls primary school, later transformed into the Olginsky three-year school.

The organization of women's education in Ossetia became possible thanks primarily to the democratic nature of the traditional culture of the Ossetians. Care for women's education was a consequence of the important social role assigned to women in Ossetia.

The origin of the literary tradition and scientific Ossetian studies. In the first half of the XIX century. in Ossetia, there was still a small number of literate and educated people. But the modest forces of the "enlightenment" turned out to be enough to set lofty spiritual goals for society. One of these goals was the creation of literary works based on the young Ossetian writing. The founder of the Ossetian literary tradition was Ivan Yalguzidze, a natural Ossetian, a native of the Dzau Gorge of South Ossetia. The literary work of I. Yalguzidze has not been sufficiently studied. So far, researchers have only one of his works - the poem "Alguziana". The poem is a historical and literary work dedicated to the successful military campaigns of the Ossetian king Alguz. In it, I. Yalguzidze showed himself as an excellent literary narrator, who had a good command of historical material.

I. Yalguzidze was an outstanding representative of the early Ossetian enlightenment. After him, a group of Ossetian ascetics appeared in the field of education and creative activity. These included priests Alexei (Akso) Koliev, Mikhail Sokhiev, deacon Alexei Aladzhikov, teachers Solomon Zhuskaev, Yegor Karaev and Georgy Kantemirov. They were pioneers of Ossetian culture, experts in the Ossetian language, history and ethnography of their people. Devoting themselves to school education, these people at the same time laid the foundations of scientific Ossetian studies, which studied the problems of the history, language and culture of the Ossetian people. Solomon Zhuskaev, for example, was the first Ossetian ethnographer who published articles and essays about the history, traditions, life and customs of Ossetians in the Caucasian periodical press.

A major phenomenon in the culture of Ossetia was scientific activity Academician Andrei Mikhailovich Sjogren, who arrived in Vladikavkaz in 1836. An outstanding linguist took up the study of the Ossetian language. A.M. Sjogren improved the graphics of the Ossetian language, wrote the “Ossetian Grammar”, providing it with a brief Ossetian-Russian and Russian-Ossetian dictionaries. The grammar of A.M. Sjogren, which marked the beginning of scientific Ossetian linguistics, was printed in St. Petersburg. Its appearance aroused a lively interest in the Ossetian language, prompted its scientific study and practical use. Already in the middle of the 19th century, after A.M. Sjogren, the Ossetian language - the compilation of practical grammar, the Russian-Ossetian dictionary and primer - was taken up by Iosif Chepigovsky. He was assisted by the first representatives of the Ossetian creative intelligentsia.

Ossetian folklore. First publications. In the first half of the XIX century. oral folk art continued to develop. Its rich tradition has not dried up with the spread of Ossetian writing and the emergence of literary creativity. In the Ossetian written culture, monuments similar to Russian chronicles or European chronographs were not created. The lack of historical narratives of this kind was completely made up by oral "Tales", heroic songs, historical legends or stories.

A feature of the Ossetian oral tradition was the narrator's desire to accurately convey the historical reality to which the folklore work was dedicated. The artistic processing of historical plots by the narrator, as a rule, did not violate the reliability of the facts or events that took place.

In folklore works of the first half of the XIX century. real events are captured, eyewitnesses of which were storytellers. For example, the narrator reproduces the resettlement of Ossetians to the Russian border line and Mozdok against the background of the aggravated Ossetian-Kabardian relations. In these relations, he sees the main reason why the Ossetians moved to the Russian border. In the stories "Taurag", "Why Masukau and Dzaraste left Ket and settled in the vicinity of Mozdok" and others, the narrator refers to the Ossetians' desire to receive Russian patronage and protect themselves from attacks by Kabardian feudal lords.

First third of the 19th century - the time of frequent punitive expeditions sent to Ossetia by the Russian administration. Oral folk art sensitively responded to the dramatic events associated with the armed resistance of Ossetians to Russian troops. The most striking work, which reflected the struggle of the Ossetian people for freedom and independence, is the Song of Khazbi. Main character works - Khazbi Alikov, who courageously fought with Russian punishers. Khazbi is a real person, he is involved in specific historical events that took place in East Ossetia. The prominent Ossetian writer Seka Gadiev recorded the earliest oral traditions about Khazbi Alikov. According to them, Khazby died in 1812 in the town of "Duadonyastau", fighting with a detachment of the Vladikavkaz commandant, General Delpozzo. Later records of the "Song of Khazbi" link the participation of Khazbi Alikov with the battles against General Abkhazov (1830). Such a displacement of the hero from some events and his inclusion in the plot of others had its own logic. People's memory, as it were, brought together the most popular hero and the most dramatic events associated with the struggle against the establishment of an autocratic regime in Ossetia.

During the Caucasian War, small detachments from Chechnya and Dagestan often attacked settlements in Ossetia. The facts of armed clashes with these detachments were also reflected in the oral folk art of the Ossetians. The heroic song "Tsagdi Mar-dta", for example, reproduces the true events associated with the death of Ossetian Cossacks near Mozdok in a battle with one of Shamil's detachments.

Folklore also illuminated such a tragic page in the history of Ossetia as the epidemics of cholera and plague ("emyn") of the late 18th - first quarter of the 19th century. They recorded the disappearance of entire families, the death of individuals, a catastrophic decline in the population of Ossetia.

In general, folklore works of the first half of the 19th century. lies the seal of a rich creative tradition that has been developing among the Ossetian people for centuries. On the genre diversity and originality of this tradition in the 50s. 19th century drew the attention of teachers Vasily Tsoraev and Daniel Chonkadze. They were the first to record and preliminary systematize the works of Ossetian oral folk art. V. Tsoraev and D. Chonkadze handed over their materials to Academician A. A. Shifner, who published these materials in several editions in the Bulletin of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Another part of these materials was later published by V. Tsoraev and D. Chonkadze in Ossetian and Russian in the Notes of the Imperial Academy of Sciences. With their publications, two domestic enthusiasts came close to such a scientific discovery as extracting Nart legends from the treasury of Ossetian folklore - an outstanding heroic epic of the people.

MM. Bliev, R.S. Bzarov "History of Ossetia"

Ossetian language belongs to the Iranian group of Indo-European languages. To the northern part of their eastern subgroup, which today has almost completely disappeared: only Ossetian and Yagnob (one of the minor languages of Tajikistan; Ossetians do not understand this language, the closest in terms of genetic classification, remain living representatives of the northern East Iranian languages).

Ossetian goes back to the languages of the Scythians-Saks-Sarmatians-Alans, who lived north of the Black and Caspian Seas, as well as in the foothills of the Caucasus (of course, along with other nomadic and semi-nomadic tribes). There are practically no written monuments in the Alanian language - the most famous is the Zelenchuk inscription of the 10th century, made in Greek letters - it can be understood in the Digor dialect of the Ossetian language. Information about the language of the Scythians is drawn mainly from the descriptions of foreign authors - primarily from the names of prominent Scythians, whose names were often "motivated" words. There is historical and etymological evidence of close contacts between the Scythian tribes (and, at a later time, the Alans) with the ancestors of modern Hungarians and Slavs, and other peoples.

Modern the Ossetian language was formed as a result of mixing the Alanian population, who left the invasions of the Mongols and Tamerlane in the mountains of the Central Caucasus, with the aboriginal population already living in this area. At the same time, the locals switched to the language of the newcomers - bypassing, apparently, the stage of prolonged bilingualism. As a result, the language was enriched with phenomena unusual for Indo-European languages in phonology (the appearance of stop-laryngeal consonants), in morphology (a developed agglutinative case system), in vocabulary (words with a dark etymology and clearly borrowed from the Adyghe, Nakh-Dagestan and Kartvelian languages; borrowings affected including basic vocabulary that is not borrowed during ordinary contacts).

Modern Ossetian writing goes back to the alphabet created by Academician Sjögrén in 1844. The then alphabet was based on Russian graphics, but had many additional symbols, thanks to which, in general, the effect of “one phoneme - one grapheme” was achieved. In the 1920s, the Latin alphabet was introduced (as part of the big fashion for romanization and the planned translation of the Russian language into Latin). In 1938, in connection with the abolition of the course towards a world revolution, a return to Russian graphics was made, and in the new version, in addition to the “basic Cyrillic alphabet”, only one additional letter remained æ (continuous spelling a and e). This symbol can be found in Danish and Icelandic, so it is in Word - menu Insert/Symbol- and can be used on the web using the XHTML mnemonic substitution - æ (also in many programs - directly from a special keyboard layout). All other "additional" sounds are transmitted by "digraphs" ("two-digit" letters, consisting of two characters: dz, j, g, q, etc.). Since then, the writing has remained unchanged. In South Ossetia, in the 1930s, a translation was made from the Latin alphabet into the “Georgian”, i.e., writing based on the Georgian graphics ... However, in the 1950s, the Cyrillic alphabet was introduced there, which ensured the unity of the written tradition in the North and South. We have a complete table of correspondences between different systems of Ossetian writing on our website.

Dialect fragmentation insignificant. Traditionally, two dialects are distinguished: Digorsky (common in the area of the city of Digora and the village of Chikola in the west of North Ossetia-A) and Ironsky (throughout the rest of the territory). can be conditionally divided into Digorsky and Chikolinsky dialects. The Iron dialect, in turn, is divided into several dialects - conditionally three: northern (most speakers), Kudar or southern (most of the Ossetian population of South Ossetia and the interior of Georgia, southern refugees in North Ossetia, including the majority of residents of the village of Nogir under Vladikavkaz, where the descendants of the settlers of the 1920s live), Ksansky or Chsansky (Leningorsky district of South Ossetia, that is, the valley of the Ksani River). The difference between Iron and Digor is quite significant, speakers often do not understand each other (however, Digors usually speak Iron, but not vice versa). Differences between dialects affect the phonological system (as a rule, regular interruptions of consonants, a change in the quality of vowels), to some extent - vocabulary (there are more Georgian borrowings in the southern dialects, Russian roots in place of the same borrowings in the northern dialects), grammar (in the Kudar dialect there is a special the paradigm of the future tense of the verb, the particle næma is used with an additional negation, and so on). Presumably the most common is the northern form of the Iron dialect.

Literary Ossetian the language was formed on the basis of the Iron dialect (with minor lexical borrowings from Digor). The poet Konstantin (Kosta) Levanovich Khetagurov (Khetagkaty) is considered the founder of Ossetian literature. The Digor dialect also has its own literary tradition, and it is often called a dialect Digor language.

Number of speakers estimated at 400-600 thousand. Perhaps the numbers are somewhat overestimated, but it is by no means possible to call the Ossetian disappearing. The positions of this language are especially strong in South Ossetia and in a number of villages in the North. The Ossetian language is broadcast on radio and television, newspapers are published (including the full-fledged daily newspaper Ræstdzinad (Pravda) - about 15 thousand copies), books are published (mostly fiction and folklore), performances are staged, Wikipedia is developed. Recently, the Digor dialect has also been developing at the republican level: a newspaper is published in it, the Digorsky Theater has been formed, specialists in the dialect are being trained at the North Ossetian State University named after M. K. L. Khetagurova and teaching a number of subjects in the Digorsky language in the schools of the Digorsky and Irafsky districts.

Examples of texts in the Ossetian language can be found in the section of our website dedicated to a short oral story.

A short guide to reading texts:

In the actual (northern) literary norm, the letter c is read like Russian sh, but somewhat more whistling. Accordingly, h - f.

The ligature æ is read like the Russian unstressed a or o. Accordingly, a is always read clearly, openly and sufficiently lengthy.

The letter y has nothing to do with the Russian similar letter (before the reform of the 20s, this sound was transmitted through v) means an indefinite sound ("shwa"), heard, for example, in Russian "November" between b and r. Fyss - write. Tyng - very much.

U before a vowel and between vowels is pronounced like a labial-labial semi-vowel (cf. English w). Warzon - beloved, beloved; Oh, mæ warzon - oh, my beloved! (or "my favorite"). Mind your "a"!

The letters c and dz (digraphs are included in the alphabet as letters, cf. Spanish ch) are read close to Russian s and z, respectively (but, in my opinion, they are clearly shorter and with clearer articulation).

Voiceless stop consonants followed by a firm sign they are read as occlusive-laryngeal, i.e., the articulatory apparatus takes a position for pronouncing a consonant, at the same time an increased air pressure is formed in the larynx and, when the bow breaks, a sound is formed: pb, tb, cb, kb and ch.

The digraph хъ is read as the Arabic q in Qaddafi, as the Karachai-Balkar kъ - the sound is formed as [k], but the active organs here are not the tongue and palate, but the root of the tongue and uvula (tongue). Хъ is taught to pronounce through x: try to stretch out a long Caucasian x, at some point stop the air, and then pronounce x from this position.

The digraph gb is read as a voiced match x. Mæ zynarg æmbal is my dear friend/comrade. Voiced vowels at the end of a word are not stunned (at least not like in Russian).

The stress in the Ossetian language falls on the first syllable if it is formed by a “strong” vowel (o, y, e, a) and on the second, if in the first it is “weak” (s, æ). The stress is forceful, the quality of the vowel does not change. Wed the word “salam” (“hello”; c is read closer to Russian w!), where both vowels a are read openly and for the ear accustomed to the Russian language, both sound like stressed.

Possessive particles (mæ - mine, næ - ours, etc.) are included in the syntagma and are devoid of stress; thus "mæ zynargj æmbal" is pronounced in the prosodic sense as one word ("accent word"); I would put the main emphasis in this phrase on a in “zynarg”, but the nature of the Ossetian stress makes it almost imperceptible to the Russian ear. In general, one can talk about phrasal stress in Ossetian rather than about stress in each word.

A few phrases:

| northern ironic | Digorsky | translation |

| Salan! | Hey! | |

| Kuyd u? (Where u?) | Where oy? | How are you? |

| Horz. | Huarz. | Okay. |

| Chi dæ ouarza? | Ca dæ ouarzuy? | Who loves you? |

| Dæ fyd kæm and? | Dæ fidæ kæmi ’y? (from ...kæmi æy) | Where is your father? |

| Tsy kænys? | Qi kænis? | What happened to you? What are you doing? |

| Me'mbalimæ ratsu-batsu kænyn. | Me’nbali hæzzæ ratso-batso kænun. [ts=rus.ts] | I am walking with a friend (girlfriend). |

| Styr Khuytsæchuy horzæh næ uæd! | Stur Hutsæjui huærzænhæ næhe uæd! | May the grace of the Great God be ours! | Amen (uæd)! | Amen (uæd)! | May it be so! Amen! |