Features of public administration in the Time of Troubles. Influence of the Troubles on public administration in the 17th century

1. Board of Boris Godunov 2

2. The first signs of a crisis 4

3. The appearance of False Dmitry I and the death of Boris Godunov 6

4. Death of Fyodor Godunov and accession of False Dmitry I 11

5. Overthrow of False Dmitry I 14

6. The accession of Vasily Shuisky 17

7. The uprising of Bolotnikov and the appearance of False Dmitry II 20

8. Polish intervention 22

9. Deposition of Vasily Shuisky and the "Seven Boyars" 24

10. The expulsion of the invaders and the accession of the Romanovs 25

11. End of the Troubles

List of used literature 27

1. Board of Boris Godunov.

The term "Time of Troubles" in Russian history refers to the period from 1604 to 1613, characterized by a severe political and social crisis of the Muscovy. The political prerequisites for this crisis, however, appeared long before the beginning of the Time of Troubles, namely, the tragic end of the reign of the Rurik dynasty, and the enthronement of the boyar Boris Godunov.

As you know, Boris Godunov was a close adviser to Tsar Ivan IV the Terrible in the last years of his life, and together with Bogdan Belsky had a great influence on the tsar. Godunov and Belsky were next to the tsar in the last minutes of his life, and from the porch they announced the death of the sovereign to the people. After John IV, his son, Fyodor Ioannovich, became king, weak and weak-willed, unable to rule the country without the help of advisers. To help the tsar, the Regency Council was created, which included: Belsky, Yuryev, Shuisky, Mstislavsky and Godunov. Through court intrigues, Godunov managed to neutralize his ill-wishers: Shuisky (sent into exile in 1586, where he was killed two years later) and Mstislavsky (expelled from the Regency Council in 1585, and died in disgrace), and occupy a dominant position in the council. In fact, since 1587, Boris Godunov ruled the country alone.

Godunov could not help but understand that his position in power was stable only as long as Tsar Fyodor was alive. In the event of Fedor's death, the throne was to be succeeded by his younger brother, the son of John IV, Tsarevich Dimitri, and given the tsar's poor health, this could not have happened in the very distant future. In all likelihood, Godunov did not expect anything good for himself from the change of the sovereign. One way or another, but in 1591, Tsarevich Dimitri died in an accident. The investigation into this case was led by the boyar Vasily Shuisky, who came to the conclusion that the prince was playing with his peers with knives when he had an epileptic seizure. Accidentally falling on a knife, the prince stabbed himself to death with this knife. He lived in the world for a little over eight years.

Godunov's contemporaries had no doubt that this accident was in fact a disguised political murder, since it was clearing the way for Godunov to the throne. Indeed, Tsar Fyodor had no sons, and even his only daughter died at the age of one. Given his poor health, it was very likely that the king himself would not live long. As subsequent events showed, this is exactly what happened.

On the other hand, Godunov's guilt in the death of Dimitri does not seem so obvious. Firstly, Demetrius was the son of the sixth wife of John IV, and the Orthodox Church, even today, recognizes only three consecutive marriages as legal (“By allowing repeated marriages of laity, the Orthodox Church does not equate them with the first,“ virgin ”marriage. , she limited the recurrence of marriage to only three cases, and when one emperor (Leo the Wise) married for the fourth time, the Church did not recognize the validity of his marriage for a long time, although it was needed in the state and dynastic interests. for this marriage ended with an act categorically prohibiting the fourth marriage for the future "). For this reason, formally speaking, Demetrius could not be considered the legitimate son of John IV, and therefore could not inherit the throne. Secondly, even in the case of the removal of Dimitri, the prospects of Godunov himself to take the throne were vague - he was neither the most noble, nor the richest of possible contenders, and the fact that he eventually became king is largely happy accident.

One way or another, in the eyes of contemporaries, this death was so into the hands of Godunov that few doubted his guilt. The death of Tsarevich Dimitri became a real mine laid under the regime of Boris Godunov, and this mine was destined to explode twelve years later, in 1603, not without the help of "friends of Russia" from outside.

In 1598, the nominal sovereign, Fyodor Ioannovich, died, and Godunov was left alone with the growing ill will of the nobility. Driven into a corner, he nevertheless managed to find an unexpected solution: he tried to secure the throne for the widow of Tsar Fyodor - Irina Godunova, his sister. According to the text of the oath promulgated in the churches, the subjects were asked to take an oath of allegiance to Patriarch Job and the Orthodox faith, Queen Irina, ruler Boris and his children. In other words, under the guise of an oath to the church and the queen, Godunov actually demanded an oath to himself and his heir.

The case, however, did not burn out - at the insistence of the boyars, Irina renounced power in favor of the Boyar Duma, and retired to the Novodevichy Convent, where she was tonsured. Nevertheless, Godunov did not give up. He, apparently, well understood that it was impossible for him to openly compete with the more noble contenders for the empty throne (primarily the Shuiskys), so he simply retired to the well-fortified Novodevichy Convent, from where he watched the split struggle for power by the Boyar Duma.

Thanks to Godunov's intrigues, the Zemsky Sobor in 1598, at which his supporters were in the majority, officially called him to the throne. This decision was not approved by the Boyar Duma, but the counter-proposal of the Boyar Duma - to establish a boyar rule in the country - was not approved by the Zemsky Sobor. A stalemate arose in the country, and as a result, the question of succession to the throne was removed from the Duma and Patriarchal Chambers to the square. The opposing parties used all possible means - from agitation to bribery. Going out to the crowd, Godunov, with tears in his eyes, swore that he did not even think of encroaching on "the highest royal rank." The motives behind Godunov's rejection of the crown are easy to understand. First, he was embarrassed by the small size of the crowd. And secondly, he wanted to end the accusations of regicide. To more accurately achieve this goal, Boris spread the rumor about his imminent tonsure as a monk. Under the influence of skillful agitation, the mood in the capital began to change.

The patriarch and members of the council tried to use the emerging success. Persuading Boris to accept the crown, the churchmen threatened to resign if their petition was rejected. The boyars made a similar statement.

The general cry created the appearance of a nationwide election, and Godunov, prudently choosing a convenient moment, generously announced to the crowd his consent to accept the crown. Wasting no time, the patriarch led the ruler to the nearest monastery cathedral and named him the kingdom.

Godunov, however, could not accept the crown without an oath in the Boyar Duma. But the older boyars were in no hurry to express their loyal feelings, which forced the ruler to retire to the Novodevichy Convent for the second time.

On March 19, 1598, Boris convened the Boyar Duma for the first time to resolve the accumulated cases that did not tolerate delay. Thus, Godunov de facto began to fulfill the functions of the autocrat. Having received the support of the capital's population, Boris broke the resistance of the feudal nobility without bloodshed and became the first "elected" king. The first years of his reign did not bode well.

“The first two years of this Reign seemed to be the best time for Russia since the 15th century or since its restoration: she was at the highest level of her new power, secure with her own strength and the happiness of external circumstances, but inside she was ruled with wise firmness and extraordinary meekness. Boris fulfilled the vow of a royal wedding and rightly wanted to be called the father of the people, reducing its burdens; the father of the orphan and the poor, pouring out on them unparalleled generosity; friend of humanity, without touching the life of people, without staining the Russian land with a single drop of blood and punishing criminals only with exile. Merchants less shy in trade; an army showered with awards in peaceful silence; Nobles, commanding people, distinguished by signs of mercy for zealous service; Synclit, respected by the active and loving Tsar; The clergy, honored by the pious Tsar - in a word, all state states could be satisfied for themselves and even more satisfied for their fatherland, seeing how Boris in Europe and Asia exalted the name of Russia without bloodshed and without painful exertion of her strength; how he cares about the common good, justice, order. And so it is not surprising that Russia, according to the legend of contemporaries, loved its Crown-bearer, wanting to forget the murder of Demetrius or doubting it! "

Nothing foreshadowed trouble, and there were only six years left before the Time of Troubles.

2. The first signs of a crisis.

The crisis was initiated by successive crop failures in 1601 and 1602. Throughout the summer of 1601, heavy cold rains fell across eastern Europe, beginning in July, mixed with sleet. The entire crop, of course, was lost. According to the testimony of contemporaries, at the end of August 1601, snowfalls and blizzards began, sleigh rides along the Dnieper, as if in winter.

“Among the natural abundance and wealth of the fertile land, inhabited by hardworking farmers; amid the blessings of a long-term peace, and in an active, prudent Reign, a terrible execution fell on millions of people: in the spring, in 1601, the sky was darkened by thick darkness, and the rains poured down for ten weeks incessantly so that the villagers were horrified: they could not do anything engage in, neither mow nor reap; and on August 15, severe frost damaged both green bread and all unripe fruits. There was also a lot of old bread in the barns and in the threshing floors; but the farmers, unfortunately, sowed the fields with new, rotten, skinny ones, and did not see any shoots, neither in autumn nor in spring: everything rotted away and mixed with the earth. In the meantime, the stocks have run out, and the fields have already remained unseeded. "

This was repeated, albeit on a smaller scale, in 1602. As a result, even the warm summer of 1603 did not help, since the peasants simply had nothing to sow - due to two past crop failures, there were no seeds.

To the credit of Godunov's government, it tried to mitigate the consequences of crop failures as best it could by distributing seeds to farmers for planting, and regulating the price of bread (up to the creation of a kind of "food detachments" that reveal hidden stocks of grain and force them to sell at a price set by the government). To give work to hungry refugees, Godunov began to rebuild the stone chambers of the Moscow Kremlin (“... in 1601 and 1602, on the site of the broken wooden palace of Ioannov, he built two large stone chambers to the Golden and Faceted ones, a dining room and a memorial room to provide them with work and food for people to the poor, combining benefit with mercy, and during the days of crying thinking of greatness! "). He also issued a decree that all slaves, left by their masters without means of food, automatically receive freedom. But these measures were clearly not enough. About a third of the country's population became victims of famine. Fleeing from hunger, people fled en masse "to the Cossacks" - to the Don and to Zaporozhye. It must be said that the policy of "pushing out" criminal and potentially unreliable elements to the north-western borders was practiced by John IV, and was continued by Godunov ("Even John IV, wanting to populate the Lithuanian Ukraine, the land of Severskaya, with people fit for military affairs, did not interfere criminals who escaped execution there to take refuge and live in peace: for he thought that in case of war they could be reliable defenders of the border.Boris, loving to follow many of the Ioannovs' state thoughts, followed this one, which was very false and very unfortunate: for Unknowingly, he made a large squad of villains to serve the enemies of the fatherland and his own. "). Indeed, all this huge mass on the borders of Russia has become a dangerous combustible material, ready to flare up from the slightest spark.

These crop failures naturally ended with the peasant uprising of 1603 under the leadership of Ataman Khlopok. The peasant army was heading for Moscow, and it was possible to defeat it only at the cost of heavy losses of government troops, and the governor himself, Ivan Basmanov, died in battle. Ataman Khlopok was taken prisoner and, according to some sources, died of his wounds, according to others, he was executed in Moscow.

In addition to peasant unrest, Godunov's life was constantly poisoned by conspiracies of the nobility, both genuine and imagined. One might think that Godunov contracted paranoia from his first patron - Tsar John IV. In 1601, his old colleague and friend Bogdan Belsky was repressed - Godunov ordered to torture him, after which he was exiled to "one of the lower towns", where he remained until Godunov's death. The reason for the repression was a trifling denunciation of Belsky from his servants - as if he, serving as a governor in the city of Borisov, allowed himself to joke: "Boris is the Tsar in Moscow, and I am the Tsar in Borisov." An uncomplicated joke cost Belsky very dearly.

In the same year, 1601, a larger-scale process was started against the Romanov family, as well as their supporters (Sitsky, Repnins, Cherkassky, Shestunovs, Karpovs ...). “The grandee Semyon Godunov, invented a way to convict the innocent of villainy, hoping for general gullibility and ignorance: he bribed the treasurer of the Romanovs, gave him sacks filled with roots, ordered him to hide Alexander Nikitich in Boyarin’s pantry and inform their masters that they were secretly working on the composition poison, plotting on the life of the Crown Bearer. Suddenly anxiety arose in Moscow: Synclitus and all the noble officials were hurrying to the Patriarch; send roundabout Mikhail Saltykov for a search in the storeroom at Boyarin Alexander; they find sacks there, carry them to Job, and in the presence of the Romanovs they pour out the roots, as if magic, made to poison the Tsar. " The consequences of this provocation were for the Romanovs and their supporters the most sad - they were all partly forcibly tonsured into monks, partly exiled, their property was confiscated.

“The Romanovs were not the only bogeyman for Borisov's imagination. He forbade the Princes of Mstislavsky and Vasily Shuisky to marry, thinking that their children, according to the ancient nobility of their kind, could also compete with his son for the throne. Meanwhile, eliminating the future imaginary dangers for the young Theodore, the timid destroyer trembled the real ones: worried about suspicions, constantly fearing secret villains and equally fearing to deserve popular hatred by torture, he persecuted and pardoned: he exiled the Voevoda, Prince Vladimir Bakhteyarov forgave him; removed from the affairs of the famous Clerk Shchelkalov, but without obvious disgrace; several times he removed the Shuiskys, and again brought them closer to him; caressed them, and at the same time threatened with disfavor to everyone who had dealings with them. There were no solemn executions, but they killed the unfortunate in dungeons, tortured them on denunciations. A host of well-known people, if not always awarded, but always free from punishment for lies and slander, strove to the Royal Chambers from the Boyars' houses and huts, from monasteries and churches: servants reported on masters, Inoki, Priests, Clerks, maltrels on people of all ranks - the most wives for husbands, the most children for fathers, to the horror of mankind! “And in the wild Hordes (adds the Chronicler) there is no such great evil: the gentlemen did not dare to look at their servants, nor their neighbors sincerely speak among themselves; and when they spoke, they mutually pledged with a terrible oath not to change their modesty. " In a word, this sad time of Borisov's reign, yielding to John in bloodsucking, was not inferior to him in lawlessness and debauchery "

There is nothing surprising in the fact that Godunov so diligently tried to eliminate, or at least remove those who could challenge the throne from him, that is, more ancient or noble boyar families. Unsure of his own right to the throne, he did everything possible to ensure the transfer of the throne to his heir, and to create conditions where nothing would threaten the new dynasty he founded. These motives were colorfully described by A.K. Tolstoy in his poem Tsar Boris, and Pushkin in the tragedy Boris Godunov.

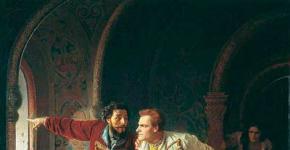

3. The appearance of False Dmitry I and the death of Boris Godunov

The popularity of Godunov among the people fell sharply, and a series of disasters revived rumors, which were already circulating among the people, that Boris Godunov was not a legitimate tsar, but an impostor, and that is why all these troubles arise. The real tsar - Dimitri - is actually alive, and is hiding somewhere from Godunov. Of course, the authorities tried to fight the spread of rumors, but they did not have much success. There is also a hypothesis that some boyars who were dissatisfied with Godunov's rule, primarily the Romanovs, had a hand in the spread of these rumors. In any case, the people were mentally prepared for the appearance of the "miraculously resurrected" Demetrius, and he was not slow to appear. "As if by a supernatural action the shadow of Dimitriev came out of the coffin in order to strike with horror, madden the murderer and confuse the whole of Russia."

According to the generally accepted version, a certain “poor boyar son, Galician Yuri Otrepiev” tried to impersonate Dimitri, who “... in his youth lost his father, in the name of Bogdan-Yakov, a streltsy centurion, stabbed to death in Moscow by a drunk Litvin, served in the house of the Romanovs and Prince Boris Cherkassky; knew literacy; showed much intelligence, but little prudence; bored with a low state and decided to seek the pleasure of careless idleness in the rank of Inok, following the example of his grandfather, Zamyatny-Otrepiev, who had long been a monk at the Chudovskaya monastery. Tonsted by Vyatka Abbot Tryphon and named Gregory, this young Chernets wandered from place to place; lived for some time in Suzdal, in the monastery of St. Euphemia, in the Galician John the Baptist and in others; finally, in the Chudov Monastery, in the cell of his grandfather, under the command. There Patriarch Job recognized him, ordained him to the Deacon and took him to him for the book business, for Gregory was able not only to copy well, but even to compose canons to the Saints better than many old scribes of that time. Taking advantage of Job's grace, he often went with him to the palace: he saw the splendor of the Tsar and was captivated by it; expressed extraordinary curiosity; eagerly listened to reasonable people, especially when the name of Dimitri Tsarevich was pronounced in sincere, secret conversations; wherever he could, he found out the circumstances of his unhappy fate and wrote it down on the charter. A wonderful thought had already settled and ripened in the soul of the dreamer, instilled in him, as they say, by one evil Monk: the idea that a brave impostor can take advantage of the gullibility of the Russians, touched by the memory of Demetrius, and execute a holy killer in honor of Heavenly Justice! The seed fell on the fruitful earth: the young Deacon diligently read the Russian chronicles and immodestly, albeit jokingly, would sometimes say to the Chudov Monks: "Do you know that I will be Tsar in Moscow?" Some were laughing; others spat in his eyes, as if I were lying to an impudent one. These or similar speeches reached the Rostov Metropolitan Jonah, who announced to the Patriarch and the Tsar himself that “the unworthy Monk Gregory wants to be the vessel of the devil”; The good-natured Patriarch did not respect the Metropolitan's answer, but the Tsar ordered his Clerk, Smirnov-Vasiliev, to send the madman Gregory to the Solovki, or to the Belozersk desert, as if for heresy, for eternal repentance. Smirnoy told about this to another Dyak, Evfimiev; Evfimiev, being a relative of the Otrepievs, begged him not to rush to fulfill the Tsar's decree and gave a way for the disgraced Deacon to flee (in February 1602), together with two Monks of Chudovsky, Priest Varlaam and Kryloshanin Misail Povadin. ". Having judiciously judged how such statements could be fraught with him within the Russian borders, Otrepiev decided to flee to where he would be welcome - to Poland (more precisely, the Commonwealth is a powerful state that occupied the current territories of Poland, the Baltic states, Belarus, part of Ukraine and the western regions of Russia ). "There, an ancient, natural hatred of Russia has always zealously favored our traitors, from the Princes Shemyakin, Vereisky, Borovsky and Tverskoy to Kurbsky and Golovin." Thus, Otrepiev's choice was quite natural, and he hoped to find help and support there. IN. Klyuchevsky writes about it this way:

“In the nest of the boyars most persecuted by Boris, with the Romanovs at the head, in all likelihood, the thought of an impostor was hatched. They blamed the Poles for setting him up; but it was only baked in a Polish oven, and leavened in Moscow. It was not for nothing that Boris, as soon as he heard about the appearance of the False Dimitry, directly told the boyars that it was their business, that they had set up the impostor. This unknown someone, who sat on the Moscow throne after Boris, arouses great anecdotal interest. His personality remains mysterious to this day, despite all the efforts of scientists to unravel it. For a long time, the prevailing opinion, coming from Boris himself, was that he was the son of a Galician petty nobleman Yuri Otrepiev, monastic Grigory. I will not tell you about the adventures of this man, which are well known to you. I will only mention that in Moscow he served as a slave for the Romanov boyars and Prince Cherkassky, then took monasticism, was taken to the patriarch as a book-writer for his bookishness and composing praise for the Moscow miracle workers, and here suddenly from something he began to say that he probably would and the king in Moscow. For this he was to die in a distant monastery; but some strong people covered him, and he fled to Lithuania at the very time when disgrace fell on the Romanov circle. "

Otrepiev's life path from the moment of his flight to the moment he appeared in the Commonwealth at the court of Prince Vishnevetsky is covered with darkness. According to N.M. Karamzin, before declaring himself a miraculously saved Tsarevich Dimitri, Otrepiev settled in Kiev, in the Pechersk monastery, where “... led a seductive life, despising the charter of abstinence and chastity; he boasted of freedom of opinion, loved to talk about the Law with the Gentiles, and was even in close connection with the Anabaptists. " But such a monastic life, apparently, bored him, since from the Pechersky monastery he went to the Zaporozhye Cossacks, to the ataman Gerasim Evangelik, where he received military skills. However, he did not stay with the Cossacks either - he left and showed up at the Volyn school, where he studied Polish and Latin grammar. There he was noticed and recruited into the service of a wealthy Polish tycoon, Prince Adam Wisniewiecki. Probably, he managed to achieve the location of Vishnevetsky, who appreciated his knowledge and military skills.

Despite Vishnevetsky's good attitude to Otrepiev, it was unthinkable for that simply to show up to the magnate and tell about his "miraculous salvation" - it is clear that no one would have believed such nonsense. Otrepiev decided to act more subtly.

“Having earned the attention and kind disposition of the master, the cunning deceiver pretended to be sick, demanded a Confessor, and said to him quietly:“ I am dying. Commit my body to the earth with honor, as the children of the Tsars are buried. I will not declare my secret until the grave; when I close my eyes forever, you will find a scroll under my bed, and you will know everything; but don't tell others. God has judged me to die in misfortune. " The confessor was a Jesuit: he was in a hurry to inform Prince Vishnevets of this secret, and the curious Prince was in a hurry to find out it: he searched the bed of the imaginary dying man; found a paper prepared in advance and read in it that his servant was Tsarevich Dimitri, saved from murder by his faithful physician; that the villains sent to Uglich killed one son of the Priest, instead of Demetrius, who was hid by the good grandees and clerks of the Shchelkalovs, and then escorted to Lithuania, fulfilling the order of the Ioannians given to them in this case. Vishnevetsky was amazed: he still wanted to doubt, but could no longer, when the cunning man, blaming the Confessor's immodesty, opened his chest, showed a gold cross strewn with precious stones (probably stolen somewhere) and with tears announced that this shrine was given to him by the Godfather Prince Ivan Mstislavsky ".

It is not entirely clear whether Vishnevetsky was really deceived, or whether he simply decided to take advantage of the opportunity that came up for his political goals. In any case, Vishnevetsky told the Polish king Sigismund III about his unusual guest, and he wished to see him in person. Prior to that, Vishnevetsky also managed to prepare the ground by spreading information about the "miraculous salvation of John's son" throughout Poland, in which he was assisted by his brother Konstantin Vishnevetsky, Constantine's father-in-law, the Sandomierz governor Yuri Mnishek, and the papal nuncio Rangoni.

There is a version, partly confirmed by documents, that initially the Vishnevetskys planned to use Otrepiev in their plans for a palace coup, aimed at the deposition of Sigismund III, and the enthronement of "Demetrius". He, being like a descendant of John IV, Rurikovich, and therefore a relative of the Polish Jagiellonian dynasty, was quite suitable for this throne. But for some reason, it was decided to abandon this plan.

King Sigismund treated the "resurrected Demetrius" coolly, like many of his dignitaries. Hetman Jan Zamoyskiy, for example, spoke about this in the following way: “It happens that the dice in the game falls and happily, but usually it is not advised to put expensive and important items on the line. This is a matter of such a nature that it can harm our state and disgrace the king and all our people. " However, the king nevertheless received Otrepiev, treated him politely (Karamzin says that he received him standing in his office, that is, recognizing him as an equal), and assigned him a monetary allowance of 40,000 zlotys annually. Otrepiev did not receive any other help from the king, but given the political situation in the then Commonwealth, he could not provide it. The fact is that the king in the Commonwealth was mainly a nominal figure, while real power belonged to the aristocracy (Vishnevets, Pototsky, Radziwills and other rich and noble houses). In the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth there was also no royal army, as such - only the infantry of 4000 guards, supported by the personal income of the king. Thus, the recognition of "Demetrius" by the king had only moral and political significance.

Otrepiev also had other important meetings, including with representatives of the Catholic Jesuit order, which had great influence in the Commonwealth. He even wrote a letter to the then Pope of Rome, Clement VIII, in which he promised in the event of his "return to the throne" to join the Orthodox Church to the Catholic one, and received a reply with "confirmation of his readiness to assist him with all the spiritual authority of the Apostolic Viceroy." To strengthen relations, Otrepiev made a solemn promise to Yuri Mnishek to marry his daughter Marina, and even officially turned to King Sigismund for permission to marry.

Encouraged by their success, the Vishnevetskys began to gather an army for a campaign against Moscow, with the goal of elevating "Demetrius" to the throne. Karamzin writes: “In fact, it was not an army, but a bastard, who took up arms against Russia: very few noble nobles, to please the King, little respected, or seduced by the thought of brave for the exiled Tsarevich, appeared in Sambir and Lvov: vagabonds were striving there, hungry and half naked, demanding weapons not for victory, but for plunder, or the salary that Mnishek generously gave out in the hope of the future. " In other words, the army consisted mainly of the very refugees, Zaporozhye and Don Cossacks, who at one time fled from Russia as a result of the policies of John IV and Boris Godunov, although some Polish gentry with their squads also joined the army being formed. Not everyone, however, was tempted by the opportunity to take revenge on the hated Godunov - as Karamzin writes, there were many who did not want to participate in the intervention, or even actively opposed it. “It is noteworthy that some of the Moscow fugitives, the Boyarsky children, filled with hatred for Godunov, while hiding in Lithuania, did not want to be participants in this enterprise, because they saw deception and abhorred evil: they write that one of them, Yakov Pykhachev, even publicly, and in the presence of the King, he testified about this gross deception, together with his comrade unstrigin, Monk Barlaam, disturbed by his conscience; that they did not believe them and sent both shackled to Voevoda Mniszka in Sambor, where they imprisoned Varlaam, and Pykhachev, accused of intending to kill False Dmitry, was executed. "

These preparations could not pass unnoticed by Godunov. Of course, the first thing that occurred to him was the assumption about the next intrigues of his enemies from among the boyars. Judging by his further actions, he was greatly frightened by the "resurrection" of Tsarevich Dimitri. To begin with, he ordered to deliver to him the mother of Demetrius, Martha Nagaya, who had long been tonsured as a nun and placed in the Novodevichy Convent. He was interested in only one question - whether her son is alive or dead. Martha Nagaya, seeing what fear the shadow of her son instilled in Godunov, undoubtedly not without pleasure, answered: “I don’t know.” Boris Godunov flew into a rage, and Martha Nagaya, wishing to enhance the effect of her answer, began to say that she had heard that her son was secretly taken out of the country, and the like. Realizing that it was impossible to get any sense out of her, Godunov stepped back from her. Soon he, nevertheless, managed to establish the identity of the impostor, and he ordered the story of Otrepiev to be made public, since further silence was dangerous, as it prompted the people to think that the impostor and truly escaped Tsarevich Dimitri. At the same time, an embassy was sent to the court of King Sigismund, led by the impostor's uncle Smirnov-Otrepiev, whose purpose was to expose the impostor; another embassy, headed by the nobleman Khrushchev, was sent to the Don to the Cossacks to persuade them to retreat. Both embassies were unsuccessful. “The Royal nobles did not want to show False Dmitry Smirnov-Otrepiev and dryly replied that they did not care about the alleged Tsarevich of Russia; and the Cossacks seized Khrushchov, shackled him and brought him to the Pretender. " Moreover, in the face of imminent death, Khrushchov fell to his knees before the impostor, and recognized him as Tsarevich Dimitri. The third embassy with the nobleman Ogarev was sent by Godunov directly to King Sigismund. He received the ambassador, but answered his requests that he himself, Sigismund, did not stand for the impostor and was not going to violate the peace between Russia and the Commonwealth, but he also could not be responsible for the actions of individual gentry who supported Otrepiev. Ogarev had to return to Boris Godunov with nothing. In addition, Godunov demanded that Patriarch Job write a letter to the Polish clergy, in which it was confirmed by the seals of the bishops that Otrepiev was a fugitive monk. The same letter was sent to the Kiev governor, Prince Vasily of Ostrog. The patriarch's messengers who delivered these letters were probably captured on the way by Otrepiev's people, and did not achieve their goal. “But the patriarchs' messengers did not return: they were detained in Lithuania and neither the Clergy nor the Prince of Ostrog answered Job to Job, for the Pretender had already acted with brilliant success. "

The invasion army was concentrated in the vicinity of Lvov and Sambir, in the possessions of the Mnisheks. Its core consisted of gentry with squads, well trained and armed, but very small in number - about 1,500 people. The rest of the army was made up of refugees who joined him, as Karamzin writes, "without a device and almost without weapons." At the head of the army were Otrepiev himself, Yuri Mnishek, the magnates Dvozhitsky and Neborsky. Near Kiev, they were joined by about 2,000 Don Cossacks and the militia gathered in the vicinity of Kiev. On October 16, 1604, this army entered Russia. At first, this campaign was successful, several cities were taken (Moravsk, Chernigov), and Novgorod-Seversky was besieged on November 11.

An experienced and brave military leader Pyotr Basmanov was sent to Novgorod-Seversky Godunov, who managed to organize an effective defense of the city, as a result of which the storming of the city by Otrepiev's army was repulsed, with heavy losses for the storming forces. “Otrepiev also sent Russian traitors to persuade Basmanov, but it was useless; wanted to take the fortress with a bold attack and was repelled; I wanted to destroy its walls with fire, but did not manage to do that either; he lost many people, and saw the calamity before him: his camp was sad; Basmanov gave time to Borisov's army to take up arms and an example of unkindness to other city governors. " "An example of unkindness", however, was not picked up by other "mayors" - on November 18, the Putivl governor, Prince Rubets-Mosalsky, together with the clerk Sutupov, went over to Otrepiev's side, arrested Godunov's emissary of the devious Mikhail Saltykov, and surrendered Putivl to the enemy. The cities of Rylsk, Sevsk, Belgorod, Voronezh, Kromy, Livny, Yelets also surrendered. Besieged in Novgorod-Seversky Basmanov, seeing the despair of his situation, began negotiations with Otrepiev, and promised him to surrender the city in two weeks. In all likelihood, he was trying to stall for time, waiting for reinforcements gathered in Bryansk by the voivode Mstislavsky.

At this time, clouds continued to gather over Godunov. Neither the testimony of Vasily Shuisky on the Execution site in Moscow helped that Tsarevich Dimitri was for certain dead (Shuisky was the head of the commission that investigated the death of Dimitri), nor the letters sent to the cities by Patriarch Job. “Until 1604, none of the Russians doubted the murder of Demetrius, who was growing up in front of his Uglich’s eyes and whom he saw all of Uglich dead, sprinkling his body with tears for five days; consequently, the Russians could not reasonably believe the resurrection of the Tsarevich; but they didn’t like Boris! ... Shuisky's shamelessness was still in fresh memory; they also knew Job's blind devotion to Godunov; they only heard the name of the Tsarina-Nun: no one saw her, no one spoke to her, again imprisoned in the Vyksinskaya Desert. Still not having an example in the history of the Pretenders and not understanding such a daring deception; loving the ancient tribe of Kings and eagerly listening to secret stories about the imaginary virtues of False Dmitry, the Russians secretly conveyed to each other the idea that God, by some miracle worthy of His justice, could save John's son for the execution of the hated predator and tyrant. " As a last resort, by order of Godunov, Patriarch Job ordered in all churches to read memorial prayers for Tsarevich Dimitri, while Grigory Otrepiev was ordered to be excommunicated and damned. However, apparently not too much hoping for the effectiveness of these means, Godunov ordered to announce something like mobilization - from every two hundred quarters of the cultivated land to put up a fully armed equestrian warrior - threatening to confiscate land and property for failure to comply with his order. "These measures, threats and punishments in six weeks united up to fifty thousand horsemen in Bryansk, instead of half a million, in 1598, militia with the invocation of the Tsar, whom Russia loved!" In other words, these measures were not successful either.

It is interesting that the king of Sweden, who was at war with the Commonwealth, offered military assistance to Godunov. To this Godunov replied that Russia does not need "the help of foreigners", and that under John, Russia successfully fought against Sweden, Poland, and Turkey, and was not afraid of the "contemptible rebel". He probably reasoned that a handful of Swedish soldiers would not help in this war anyway.

On December 18, the Russian army reached from Bryansk to Novgorod-Seversky, where Otrepiev's army besieged the city, but did not dare to attack outright, and camped nearby. For three days, neither Otrepiev nor the Russian commanders dared to make the first move; finally, on December 21, a battle took place. During the battle, the Polish cavalry managed to break through the line of Russian troops in the center, the voivode Mstislavsky was seriously wounded, and only his personal squad saved him from being captured. The situation was straightened out by the blow of German mounted mercenaries who attacked from the left flank, and finally saved the Russian army from defeat by the governor Basmanov, who left the city with an army and struck the enemy in the rear. Otrepiev, seeing that this battle could no longer be won, ordered his troops to withdraw from the battle.

The next day, the Russian army withdrew to Starodub-Seversky for regrouping. The impostor's army, also badly battered, retreated to Sevsk, taking up defenses in it. The situation again became a stalemate - no one could decide to be the first to resume hostilities. For a long time the Russian commanders did not dare to inform Godunov about the results of the battle, and when he learned about its results from others, he sent his close chaplain Velyaminov to the wounded Mstislavsky to declare personal gratitude to Mstislavsky. “When you, having completed the famous service, see the image of the Savior, the Mother of God, the Miracle Workers of Moscow and our Tsar's eyes: then we will grant you beyond your hopes. Nowadays, a skilled doctor is sent to you, so that you will be healthy and again on horseback. " , and 2000 rubles, a lot of silver vessels from the Kremlin treasury, a profitable estate and the dignity of Boyar Dumny ").

Basmanov's removal from the army may have been a serious mistake by Godunov. Instead of Basmanov, Prince Vasily Shuisky was appointed, who “had neither the mind nor the soul of a true, decisive and courageous leader; Convinced of the vagabond's imposture, he did not think to betray his fatherland to him, but, pleasing Boris as the flattering courtier, he remembered his disgrace and saw, perhaps, not without secret pleasure, the torment of his tyrannical heart, and wishing to save the honor of Russia, he wished the Tsar. " On January 21, a new battle took place, after which Otrepiev's army retreated to Rylsk, and then to Putivl, taking up defenses there.

The siege by Russian troops of Putivl and others that had gone over to the side of the impostor of the cities, skirmishes and sluggish fighting lasted until the spring of 1605, when on April 13, Boris Godunov unexpectedly died. The exact cause of death remains unknown. “Boris, on April 13, at one in the morning, judged and lined up with the nobles in the Duma, received noble foreigners, dined with them in the golden chamber and, as soon as he got up from the table, he felt sick: blood gushed from his nose, ears and mouth; flowed like a river. The doctors they loved so much could not stop her. He lost his memory, but managed to bless his son to the Russian State, to perceive the Angelic Image with the name of Bogolep, and two hours later gave up his ghost, in the same temple where he feasted with Boyars and with foreigners. Unfortunately, the offspring does not know anything more about this death. " There are suggestions that Godunov could have been poisoned by conspirators from among personal enemies - such assumptions were expressed by V.O. Klyuchevsky and N.I. Kostomarov. It is curious that literally a few days after Boris's death, according to the ineradicable Russian tradition, rumors spread that instead of Godunov there was a “wrought iron angel” in the coffin, and the tsar himself was alive and was hiding somewhere or wandering. True, these rumors very quickly died out by themselves.

4. Death of Fyodor Godunov and accession of False Dmitry I

After the death of Boris Godunov, his son Fyodor took the throne. Since he was very young (16 years old), it was decided to withdraw from the army to help him experienced nobles - the princes of Mstislavsky, and Vasily and Dmitry Shuisky. Also, restoring justice, Bogdan Belsky was returned from exile. Pyotr Basmanov was appointed chief commander "for there were no doubters either in his military talents, or in loyalty, proved by his brilliant deeds." This turned out to be the first serious mistake Fedor and his advisers made. It is still not clear what could have pushed Basmanov, treated kindly by the Godunovs, to the path of treason, but the facts are such that, after returning to the army, he entered into negotiations with Otrepiev, and, in the end, went over to his side.

“Surprising contemporaries, Basmanov’s case also surprises posterity. This man had a soul, as we shall see in the fateful hour of his life; did not believe the Pretender; so zealously denounced him and so courageously struck him under the walls of Novgorod Seversky; was showered with the favors of Boris, was awarded the entire power of attorney of Theodore, was chosen to be the savior of the Tsar and the Kingdom, with the right to their unlimited gratitude, with the hope of leaving a brilliant name in the annals - and fell at the feet of the defrocked in the form of a vile traitor? Can such an incomprehensible action be explained by the poor disposition of the army? Let's say that Basmanov, foreseeing the inevitable triumph of the Pretender, wanted to save himself from humiliation by accelerating treason: he wanted to give up both the army and the Kingdom to the deceiver, rather than be given to him by the rebels? But the regiments still swore by the name of God in fidelity to Theodore: with what new zeal could the Voevoda of goodness inspire them, by the power of his spirit and law, curbing the evil-minded? No, we believe the legend of the Chronicler that it was not a general betrayal that attracted Basmanov, but Basmanov made a general betrayal of the army. This ambitious without the rules of honor, greedy for the pleasures of the temporary worker, thought, probably, that the proud, envious relatives of Theodorovs would never yield to him the closest place to the throne, and that the Rootless Pretender, who was elevated to the Kingdom by him (Basmanov), would naturally be tied by gratitude and his own benefit. to the main culprit of their happiness: their fate became inseparable and who could outshine Basmanov with personal virtues? He knew other Boyars and himself: he didn’t only know that the strong in spirit fall like babies on the path of lawlessness! Basmanov probably would not have dared to betray Boris, who acted on the imagination with the long-term domination and brilliance of the great state mind: Theodore, weak in his youth and the news of statehood, instilled courage in a traitor armed with superstition to calm his heart: he could think that treason saves Russia from the hated oligarchy of the Godunovs, handing over the scepter to the Pretender, albeit to a man of low birth, but to a brave, intelligent, friend of the famous Polish Crown-bearer, and, as it were, chosen by Fate to perform a worthy revenge on the family of the holy-killer; could think that he would direct False Dmitry on the path of goodness and mercy: he would deceive Russia, but he would atone for this deceitful happiness! "

After Basmanov's betrayal, all hope of keeping Fyodor Godunov on the throne was lost. On June 1, 1604, messengers sent from Otrepiev were received in Moscow, where they read from the Execution Ground the impostor's appeal "to the Synclite, to the great nobles, dignitaries, clerks, military, merchant, middle and black people":

“You swore to my father not to betray his children and posterity forever and ever, but you took Godunov as Tsar. I do not reproach you: you thought that Boris killed me in my infancy; they did not know his cunning and did not dare to oppose the man who had already ruled under the rule of Theodore Ioannovich - he gave and executed whoever he wanted. Deceived by him, you did not believe that I, saved by God, was coming to you with love and meekness. Precious blood flowed ... But I regret that without anger: ignorance and fear excuse you. Fate has already been decided: the cities and my army. Will you dare to fight internecine to please Maria Godunova and her son? They do not feel sorry for Russia: they do not own theirs, but they own someone else's; they have fed the land of Severskaya with blood and want to ruin Moscow. Remember what happened from Godunov to you, Boyars, Voevods and all famous people: how much disgrace and unbearable dishonor? And you, Nobles and Boyarsky Children, what did you not endure in the burdensome services and in exile? And you, merchants and guests, how much oppression did you have in trade, and what immoderate duties did you burden? We want to bestow upon you unparalleled: Boyars and all dignitaries of honor and new fathers, Nobles and people ordered by mercy, guests and merchants with privilege in a continuous course of peaceful and quiet days. Do you dare to be adamant? But you will not get away from our Royal hand: I go and sit on my father's throne; I am going with a strong army, my own and Lithuanian, for not only Russians, but also foreigners willingly sacrifice my life. The most unfaithful Nogai wanted to follow me: I ordered them to stay in the steppes, sparing Russia. Fear death, temporary and eternal; fear the answer on the day of God's judgment: humble yourself, and immediately send the Metropolitans, Archbishops, Duma men, Great Nobles and Clerks, military and merchant people, to beat us with your foreheads, as your legitimate Tsar. "

The appeal, read from the Execution Grounds, caused great confusion among the people, and a pogrom began in Moscow. The rebels seized the Kremlin and imprisoned Fyodor Godunov, his sister Xenia, and Boris Godunov's widow Maria. The palace was plundered, like many wealthy houses in Moscow. The rebellion was pacified only after the rioters were threatened with disfavor of “Tsar Demetrius”. Supporters of the Godunovs were captured and sent to prisons in remote cities, including Patriarch Job, who was deposed and sent to the Staritsky Monastery. On June 10, Fyodor and Maria Godunov were secretly killed, and the people were told that they had committed suicide. Their bodies were buried in the monastery of St. Prokofy on Sretenka. The further fate of Ksenia Godunova is not exactly known, there are two versions. One by one, Xenia was killed along with her mother and brother; according to the second, she was imprisoned in the Vladimir monastery, where she remained until her death.

On June 20, False Dmitry entered Moscow. All the way to Moscow he was greeted by crowds of people who brought him bread and salt and rich gifts. Apparently, the people were quite sure that this was really Tsarevich Demetrius, their rightful king. After arriving in Moscow, False Dmitry demonstratively visited the Church of the Archangel Michael, in which John IV was buried, where “he shed tears and said:“ O kind parent! You left me orphaned and persecuted; but with your holy prayers I am whole and dominate! " In an effort to secure the support of the nobility by taking the throne, he first of all restored and rewarded many of those who had been repressed during the reign of Boris Godunov.

Strange as it may seem, the further actions of False Dmitry least of all resemble the actions of an adventurer concerned only with stuffing his pockets. He began to carry out government reforms.

The reforms carried out by False Dmitry were very extensive, and as far as can be judged, reminded the later reforms of Peter I. He declared freedom of trade, trades and crafts, canceling all previous restrictions. Following this, he eliminated "all sorts of constraints" for those who wanted to leave Russia, enter it or move freely around the country. There are testimonies of disinterested persons, the British, who wrote that "this was the first sovereign in Europe who made his state to such an extent free." Many were returned to the estates selected by John IV. Other princes were allowed to marry, which was forbidden at one time by the Godunovs for fear that there would be too many of those in whom the blood of Rurik was flowing. Penalties for bribes for judges were toughened, and legal proceedings were made free of charge. Foreigners who know crafts that may be useful to the state began to be invited to Russia in large numbers. In some ways, False Dmitry went even further than his predecessors: under the previous tsars, the highest Orthodox clergy was invited to the Boyar Duma only in exceptional cases, but False Dmitry gave the patriarch and bishops permanent positions there. According to the recollections of his contemporaries, the impostor presided over the Duma with visible interest and pleasure, where he solved complicated matters not without wit, and at the same time was not averse to reproaching the boyars for ignorance and offered to go to Europe to learn something useful there.

The new laws on servitude were very important. Under Godunov, a man who sold himself to be a slave, "by inheritance", along with other property, passed to the heirs of his master, moreover, all his offspring automatically became slaves. According to the decree of False Dmitry, this practice was canceled - with the death of the lord the servant received freedom, and only himself could sell himself into "bondage", his children remained free. In addition, it was decided that the landowners, who did not feed their peasants during the famine, did not dare to keep them on their lands any longer; and the landowner, who failed to catch his fugitive serf for five years, loses all rights to him.

It was False Dmitry who first began to make plans for the conquest of Crimea, which by that time had turned into a source of constant disasters for Russia. The accelerated production of weapons began, maneuvers were arranged - but with the death of False Dmitry, these plans were postponed for a long time.

Contrary to the assertions of pre-revolutionary official Russian historiography, it does not appear that False Dmitry was a puppet in the hands of Polish magnates. After False Dmitry took the throne, the Polish ambassador Gonsevsky arrived in Moscow, officially - to congratulate the new tsar on his accession to the throne. Unofficially, to remind him of the obligations given to Sigismund. However, False Dmitry refused from the territorial concessions that were once promised to the king, claiming that "he is still not firmly seated in the kingdom to make such decisions." Moreover, the impostor expressed his displeasure with the fact that the king titled him "Grand Duke" and demanded that in further correspondence he be called "the king of the emperor." In the diplomacy of the time, this was extremely important, and meant that Russia lay claim to a higher hierarchical position than the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Not surprisingly, this "little thing" has become the subject of heated debate. “Upon learning of such a proud demand, Sigismund expressed annoyance, and the Noble Pans reproached the recent tramp with ridiculous arrogance, evil ingratitude; and False Dmitry wrote to Warsaw that he had not forgotten the good offices of the Sigismundovs, that he honored him as a brother, as a father; wants to establish an alliance with him, but will not cease to demand the title of Caesar, although he does not think of threatening him with war for that. Prudent people, especially Mnishek and the Papal Nuncio, vainly argued to the Pretender that the King called him as the Polish Sovereigns always called the Sovereigns of Moscow, and that Sigismund could not change this habit without the consent of the ranks of the Republic. Others, no less prudent people, thought that the Republic should not quarrel for an empty name with a boastful friend who could be her instrument for pacifying the Swedes; but the Pans did not want to hear about the new title ... "

The same disappointment befell the emissaries of Pope Paul V, whose predecessor False Dmitry once promised the reunification of the Orthodox and Catholic Churches. And in response to the Pope's letter, in which he reminded the impostor of the promises made to his predecessor Clement VIII, he completely ignored questions of faith, and instead offered the Pope a joint campaign against the Turks. “... The pretender in a courteous answer, boasting of the wonderful goodness of God to Him, having destroyed the villain, his patricide, did not say a word about the unification of the Churches, he spoke only of his magnanimous intention to live not in idleness, but together with the Emperor to go to the Sultan in order to erase the Power infidels from the face of the earth, convincing Paul V not to allow Rudolph to make peace with the Turks, for which he wanted to send his own Ambassador to Austria. False Dimitri also wrote to the Pope a second time, promising to bring security to his Missionaries on their way through Russia to Persia and to be faithful in the fulfillment of the word given to him; negotiations about the Turkish war, which he really conceived, captivated in the imagination by its glory and benefits. " It is clearly seen that False Dmitry, in a completely uncharacteristic manner for a temporary adventurer, thinks about the welfare of his state, and is actively involved in international politics. He is completely pragmatic, and questions of faith for him in second, if not in tenth place. “The Pope… but he had reason not to trust the Pretender’s zeal for the Latin Church, seeing how he avoids any clear word about the Law in his letters. It seems that the Pretender has grown cold in his zeal to make the Russians Papists, for, despite his inherent recklessness, he saw the danger of this ridiculous plan and would hardly have dared to start fulfilling it if he had reigned longer. "

5. Overthrow of False Dmitry I.

The reign of False Dmitry lasted less than a year, namely, 331 days. During his reign, a serious conspiracy was gossiped against him, led by Prince Shuisky and his brothers Dmitry and Ivan. It is noteworthy that this conspiracy was promptly revealed, and the conspirators were arrested, put on trial and sentenced, but then False Dmitry for some reason pardoned them, replacing the death penalty with exile and confiscation of property. The impostor's mercy cost him dearly in the future. “Here the whole area boiled in an indescribable movement of joy: they glorified the Tsar, as on the first day of his solemn entry into Moscow; the faithful adherents of the Pretender rejoiced, too, thinking that such mercy gives him a new right to love in common; only the most far-sighted of them were indignant, and they were not mistaken: could Shuisky have forgotten the torture and the chopping block? " To complete his mistake, after six months from the date of the verdict, False Dmitry returned Shuisky and others from exile, taking from him a "written commitment of fidelity." Shuisky, of course, did not forgive him the fear and humiliation he had experienced, and embarked on conspiracies with renewed vigor. Peter Basmanov, loyal to False Dmitry to the end, repeatedly informed him of the signs of an impending rebellion, but he did nothing in response. “On Thursday, May 15, some Russians reported to Basmanov about the conspiracy. Basmanov reported to the tsar. “I don’t want to hear that,” said Demetrius, “I don’t tolerate informers and will punish them themselves.”

On May 17, 1606, a rebellion began in Moscow, led by Prince Vasily Shuisky. “On May 17, at four o'clock in the afternoon, the most beautiful of spring, the rising sun illuminated the terrible alarm of the capital: they first struck the bell at St. Elijah, near the courtyard of the living room, and at one time the alarm went off in whole Moscow, and residents rushed from their houses to Krasnaya square with spears, swords, samopalami, Noblemen, Boyarsky children, archers, clerks and merchants, citizens and the mob. There, near the place of execution, Boyars were sitting on horses, in helmets and armor, in full armor, and representing their fatherland, they were waiting for the people. " False Dmitry was blocked in the Kremlin, Basmanov with a small detachment of German mercenary bodyguards tried to protect him. According to eyewitnesses, in despair he turned to False Dmitry with the words: “It's all over! Moscow is rebelling, they want your head, save yourself! You didn't believe me! "

“The False Dimitri himself, showing courage, snatched the reed from Schwarzgof's bodyguard, opened the door in the hallway and, threatening the people, shouted:“ I’m not Godunov for you! ” Shots were answered and the Germans locked the door again; but there were only 50 of them, and also, in the inner rooms of the palace, 20 or 30 Poles, servants and musicians: other defenders, in this terrible hour, did not have the one to whom millions had obeyed the day before! But False Dmitry had another friend: not finding the opportunity to resist force by force, at that moment when the people were beating off the doors, Basmanov went out to him a second time - he saw Boyar in the crowd, and between them the closest people were unstripped: Princes Golitsyn, Mikhail Saltykov, old and new traitors; wanted to convince them; talked about the horror of rebellion, treachery, anarchy; convinced them to change their minds; vouched for the King's mercy. But he was not allowed to say much: Mikhailo Tatishchev, who was saved by him from exile, yelled: “villain! go to hell with your King! " and stabbed him in the heart. Basmanov gave up his ghost, and the dead was thrown from the porch "

Trying to escape, False Dmitry jumped out the window, but broke his leg and was discovered by the guard archers. Apparently, the archers and other people who turned out to be at the same time were not so sure that he was really an impostor, because they helped him: “... they took the uncut, planted on the foundation of Godunovsky's broken palace, poured water, expressed pity . " However, False Dmitry did not lose his presence of mind, and demanded from the people gathered around him, among whom were the participants in the conspiracy, to bring the widow of John IV Martha Nagoya, who would testify that he really was Demetrius. He also demanded that he be taken to Execution Ground, and there he was publicly accused of imposture. “Noise and scream drowned out the speeches; they only heard how they assure that the defrocked to the question: "who are you, the villain?" answered: "you know: I am Demetrius" - and referred to the Tsarina-Nun; We heard that Prince Ivan Golitsyn objected to him: "We already know her testimony: she is putting you to death." We also heard that the Pretender said: "Take me to the place of execution: there I will declare the truth to all people." Impatient people were pounding at the door, asking if the villain was to blame? He was told that he was guilty - and two shots ended the interrogation along with Otrepiev's life. "

CM. Soloviev sets out the following version of what happened: "While waiting for an answer from Martha, the conspirators did not want to be left alone and, with curses and beatings, asked False Dmitry:" Who are you? Who is your father? Where are you from? " He answered: "You all know that I am your king, the son of Ivan Vasilyevich. Ask my mother about me or take me to Execution Ground and let me explain." Then Prince Ivan Vasilyevich Golitsyn appeared and said that he had been with Queen Martha, asked: she says that her son was killed in Uglich, and this is an impostor. These words told the people with the addition that Demetrius himself was guilty of his imposture and that the Naked confirmed the testimony of Martha. Then shouts were heard from everywhere: "Hit him! Cut him!" The boyar's son Grigory Valuev jumped out of the crowd and shot at Demetrius, saying: "What to interpret with a heretic: here I will bless the Polish whistler!" Others killed the unfortunate man and threw his corpse from the porch onto Basmanov's body, saying: "You loved him alive, do not part with the dead either." Then the rabble took possession of the corpses and, exposing them, dragged them through the Spassky Gate to Red Square; Having caught up with the Ascension Monastery, the crowd stopped and asked Martha: "Is this your son?" She replied: "You would have asked me about this when he was still alive, now he is, of course, not mine."

After the murder of False Dmitry, a pogrom of foreigners, primarily Poles, began in Moscow. More than a thousand people were killed, not only Poles, but also Germans, Italians, and Russians who turned up at the wrong time. The pogrom ended only the next day, at 11 o'clock in the morning.

“Then Basmanov was buried at the church of St. Nicholas the Mokroi, and the impostor was buried in a wretched house outside the Serpukhov Gate, but there were various rumors: they said that severe frosts were due to the magic of the uncut, that miracles were happening over his grave; then they dug his corpse, burned it in the Cauldrons and, having mixed the ashes with gunpowder, fired them from a cannon in the direction from which he came. " Thus ended the short reign of False Dmitry.

According to the testimony of the German pastor Ber, a certain old man who was in Uglich a servant at the Tsarevich's court, when asked whether the murdered one was really Tsarevich Dimitri, answered this way: “The Muscovites swore allegiance to him and broke their oath: I do not praise them. A reasonable and brave man was killed, but not the son of Ioann, who was really stabbed to death in Uglich: I saw him dead, lying in the place where he always played. God is the judge of our Princes and Boyars: time will tell whether we will be happier. " Happier, however, did not become, as further events showed.

Who was False Dmitry really? The generally accepted version, it is also the official one, is that the fugitive deacon Otrepiev was posing as Tsarevich Dimitri. However, for example, N.I. Kostomarov objects to this in the following way: “First, if the named Dimitri was a fugitive monk Otrepiev, who fled from Moscow in 1602, then he could not have learned the techniques of the then Polish nobleman for two years. We know that the one who reigned under the name of Dimitrius rode excellently, danced gracefully, shot well, deftly wielded a saber and perfectly knew the Polish language: even in Russian, he could not hear a Moscow accent. Finally, on the day of his arrival in Moscow, applying himself to the images, he aroused the attention by his inability to do this with such methods as were customary among natural Muscovites. Secondly, the named Tsar Demetrius brought Grigory Otrepiev with him and showed him to the people. Subsequently, they said that this was not the real Gregory: some explained that it was a monk of the Krypetsky monastery, Leonidas, others that it was the monk Pimen. But Grigory Otrepiev was not at all such a little-known person that one could substitute another in his place. Grigory Otrepiev was a clerk of the cross (secretary) of Patriarch Job, with him he went with papers to the tsarist duma. All the boyars knew him by sight. Gregory lived in the Chudov Monastery, in the Kremlin, where Paphnutius was the archimandrite. It goes without saying that if the named tsar were Grigory Otrepiev, he would most of all have to avoid this Paphnutius and, above all, would try to get rid of him. But the Chudovsky Archimandrite Paphnutius during the entire reign of the named Demetrius was a member of the Senate he established and, therefore, saw the tsar almost every day. And finally, thirdly, in the Zagorovsky monastery (in Volhynia) there is a book with the signature of Grigory Otrepiev; this signature has not the slightest resemblance to the handwriting of the named Tsar Demetrius. " And further: ““ The very method of his deposition and death proves as clearly as possible that it was impossible to convict him not only of being Grigory Otrepiev, but even of imposture in general. Why kill him? Why didn't they treat him exactly as he asked: why didn't they take him out to the square, didn't they summon the one he called his mother? Why did they not present their accusations against him to the people? Why, finally, did they not summon Otrepiev's mother, brothers and uncle, gave them a confrontation with the tsar, and caught him? Почему не призвали архимандрита Пафнутия, не собрали чудовских чернецов и вообще всех знавших Отрепьева и не уличили его? That is how many extremely powerful means were in the hands of his killers, and they did not use any of them! Instead, they distracted the people, spurred him on to the Poles, they themselves killed the tsar in a crowd, and then announced that he was Grishka Otrepiev, and explained everything dark, incomprehensible in this matter by witchcraft and devilish seduction. "

The captain of foreign mercenaries Jacques Margeret, who personally knew False Dmitry, wrote about him in his memoirs: “He shone with a certain greatness that cannot be expressed in words, and never before seen among the Russian nobility and even less among people of low origin, to whom he inevitably had to belong, if it were not for the son of John Vasilyevich. " This means that he doubted that False Dmitry was Grigory Otrepiev.

Later, in the 19th century, a hypothesis appeared that False Dmitry was an unconscious tool in the hands of a certain boyar group (most likely - the Romanovs), which, having found a young man approximately suitable in age, assured him that he was the son of John who had miraculously escaped from the murderers. IV, sent him to Poland, after which she paralyzed the resistance of the government troops with finely calculated maneuvers, prepared the Muscovites, killed Godunov along with his wife and son, and later, when False Dmitry began to interfere with them, eliminated him. This hypothesis is supported by the actions taken by False Dmitry during his reign - absolutely everything in them says that he was going to rule seriously and for a long time, that he himself was confident in his rights to the throne. Even his phrase “I’m not Godunov for you!”, Shouted out by him in the heat of the battle, may mean that, unlike Godunov who appeared out of nowhere in the kingdom of Godunov, he himself has all the rights to the throne and is not going to give them to anyone. And even falling into the hands of the rebels, he does not lose his presence of mind, does not beg for mercy, but firmly demands that he be given the opportunity to turn to the people, to his mother, and to other people who could confirm his rights.

But, probably, now no one will ever know exactly how everything was in reality.

6. The accession of Vasily Shuisky

It can be assumed that Shuisky started a rebellion not only to settle accounts with False Dmitry, but also with a more far-reaching goal. “It was easy to foresee who would take this spoil by force and right. The bravest denouncer of the Pretender, miraculously saved from execution and still fearless in a new effort to overthrow him: the culprit, the Hero, the head of the popular uprising, the Prince from the tribe of Rurik, St. Vladimir, Monomakh, Alexander Nevsky; the second Boyarin with a place in the Duma, the first with the love of Muscovites and personal virtues, Vasily Shuisky could still remain a simple courtier and, after such courage, with such a celebrity, start a new service of flattery in front of some new Godunov? " In other words, he foresaw in advance that he would be the most likely candidate for the empty throne (as the most noble one, and generally glorified himself by ridding the country of the impostor). “Having strength, having the right, Shuisky also used all sorts of tricks: he gave instructions to friends and adherents, what to say in the Synclite and on the place of execution, how to act and rule minds; he prepared himself, and the next morning, having assembled the Duma, he uttered, as they say, a very clever and crafty speech: he glorified the mercy of God to Russia, exalted by the autocrats of the Varangian tribe; especially praised the mind and conquests of John IV, albeit cruel; boasted of his brilliant service and important State experience, acquired by him in this active reign; depicted the weakness of John's heir, the evil lust for power of Godunov, all the misfortunes of his time and the people's hatred of the holy killer, which was the fault of the False Dmitry's successes and forced Boyars to follow the common movement. " The few voices that said that it was necessary to assemble the Zemsky Sobor, and that it was impossible to elect a new tsar by the Boyar Duma alone, were quickly and effectively silenced. On May 19, Vasily Shuisky was elected king.

Vasily Shuisky, on which both Karamzin and Klyuchevsky agree, was, apparently, an unpleasant person. “He was an elderly, 54-year-old boyar of small stature, nondescript, half-blind, not stupid person, but more cunning than clever, utterly lying and intrigued, having gone through fire and water, having seen the chopping block and did not try it only by the grace of an impostor, against whom he acted surreptitiously, a great head-hunter and very much intimidated by sorcerers. He opened his reign with a number of letters published throughout the state, and each of these manifestos contained at least one lie. ... Nevertheless, the accession of Prince. Basil constituted an era in our political history. Ascending the throne, he limited his power, and the conditions of this limitation were formally stated in a note sent to the regions, on which he kissed the cross on accession. "

The last point is very important - Vasily Shuisky with this "record" limited the power of the autocrat, which was not previously seen in Russian history. Among other things, the tsar undertook in it the obligation "do not lay your disgrace without fault." As an expression of the master's will of the sovereign, the disgrace did not need justification, and under the previous kings it sometimes took the form of wild arbitrariness, turning from a disciplinary measure into a criminal punishment. Under John IV, a mere doubt of dedication to duty could bring the disgraced to the scaffold. Thus, Vasily Shuisky made a bold vow (which later, however, did not fulfill) to apply disciplinary punishments only for specific offenses, which, by the way, still had to be proven through a court.

In addition, the "record" said that anonymous denunciations would no longer be accepted for consideration, that a knowingly false denunciation would be punished "depending on the fault of the accused" (that is, depending on the severity of the false accusation), that cases about criminal offenses (punishable by death and confiscation of property) will be considered by the tsar's court together with the Boyar Duma. In other words, the "record" was aimed at protecting the personal and property security of subjects from arbitrariness from above.

“... Tsar Vasily renounced three prerogatives in which this personal power of the Tsar was most clearly expressed. Those were: 1) "disgraced without guilt", tsarist disfavor without sufficient reason, at personal discretion; 2) confiscation of property from the family and relatives of the criminal not involved in the crime - by renouncing this right, the old institution of political responsibility of the clan for relatives was abolished; finally, 3) an extraordinary investigative and police court on denunciations with torture and slander, but without confrontations, testimony and other means of the normal process. These prerogatives constituted the essential content of the power of the Moscow sovereign, expressed in the words of Ivan III: to whom I want, that I will give reign, and in the words of Ivan IV: we are free to grant our servants and we are free to execute them. Shaking off these prerogatives with an oath, Vasily Shuisky turned from a sovereign of slaves into a legitimate king of his subjects, ruling according to the laws. "

The reason for such a progressive step was, apparently, not the high personal qualities of Vasily Shuisky, but the simple fact that Shuisky's power did not even have the dubious legitimacy that the power of False Dmitry possessed, and certainly not the one that the power possessed. Boris Godunov, called to the kingdom by the Zemsky Sobor. Shuisky was nothing more than a creature of the Boyar Duma, a narrow circle of aristocracy, and he perfectly understood that he could be removed from the throne as easily as he was appointed to it. For this reason, he was forced to seek support in the zemstvo. “Having pledged to his comrades on the eve of the uprising against the impostor to rule by general advice with them, thrown into the earth by a circle of noble boyars, he was a boyar king, a party king, forced to look out of the hands of others. Naturally, he was looking for the Zemstvo support for his incorrect power and in the Zemstvo Cathedral he hoped to find a counterbalance to the Boyar Duma. Swearing an oath to the whole land not to punish without a council, he hoped to get rid of the boyar guardianship, become a zemstvo tsar and limit his power to an institution that was not accustomed to that, that is, to free it from any real limitation. "

In an effort to convince the people of the illegitimacy of the previous reign, Shuisky sent letters to the regions on his own behalf, in which he announced the death of False Dmitry, with an accurate statement of the reasons, in particular, he announced the papers found in the impostor. "Many exiled thieves from Poland and Lithuania about the ruin of the Moscow state were taken in his mansion." However, nothing was said about the content of these "letters" in Shuisky's letters. Shuisky also cites evidence of the impostor's promises given to Mnishek and King Sigismund about territorial concessions to Poland, and concludes: “Hearing and seeing that, we praise the almighty God that we have delivered from such villainy”. Also, on behalf of Martha Nagoya, a second letter was sent out, which said: “He called himself the son of Tsar Ivan Vasilyevich with witchcraft and witchcraft, deceived many people in Poland and Lithuania with demonic darkness, and frightened us and our relatives with death; I told the boyars, the nobles to all the people before secretly, but now it is clear to everyone that he is not our son, Tsarevich Dimitri, a thief, apostate, heretic. And when he came from Putivl to Moscow with his witchcraft and witchcraft, knowing his theft, he did not send for us for a long time, but sent his advisers to us and ordered them to take care of them so that no one would come to us and no one with us about him did not speak. And how he ordered us to bring us to Moscow, and he was with us alone at the meeting, but the boyars and other people with him did not order to let us in and told us with a great prohibition so that I would not denounce him, opposing us and our entire family to mortals murder, so that we would not bring our evil death on ourselves and on the whole family, and he put me in a monastery, and assigned his advisers to me, and ordered him to be very careful, so that his theft would not be obvious, and I declare to threaten him among the people obviously did not dare his theft. " It is noteworthy that the names of the "advisers" are not indicated, which may mean the following: either these advisers did not exist at all, or after the coup these advisers became so powerful that it was impossible to reveal their names. It is known that False Dmitry sent Prince Skopin-Shuisky for Martha, who for some reason not only did not undergo any reprisals after the overthrow of False Dmitry, but also continued a successful career at court - for example, he went to the head of the embassy to the King of Sweden, and subsequently commanded the troops that fought with False Dmitry II. Probably, during the reign of False Dmitry, he remained the man of Prince Shuisky, and probably took an active part in the conspiracy directed against him.